Video games are reaching maturity as an artform, and morality is at its crux. Notably in recent years, players have been responding to the ability to explore what a game's particular world deems as right or wrong, and in turn, the ability to imprint onto that world what they deem is right and wrong as well. And the industry is taking notice: Bioshock, Fallout, The Elder Scrolls, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Knights of the Old Republic, Fable – all of these franchises are both financially and critically successful in part because of their interpretation on moral choices. Not only are these franchises creating sequels that boast even more sophisticated morality systems, but new intellectual properties like Heavy Rain also mark morality as the new frontier for modern gaming.

Morality systems are nothing new, especially since they can be viewed as just an instance of non-linear storytelling. Having multiple dialogue options shouldn’t shock anyone and simply coloring those options with various shades of morality shouldn’t either. Yet there’s something personal when choosing among moral, immoral, and neutral choices. Ethics go straight to the core of the player, so even if the choices feel artificial or cliché in their portrayal of good and evil, they have private impact.

Moral Judgment

By letting the player choose their moral alignment, most of these games relinquish their favor for either “good” or “evil”. As opposed to other artforms like film and literature, they do no attempt to instill a specific viewpoint in its audience (a good marketing decision too), instead providing a simulation of what occurs in its world when a player follows one such viewpoint. They don’t teach players to follow “good” morals, as much as they teach them what they are conceptually. Even if players choose a “bad” action – murdering an innocent in cold blood, for instance – they do so understanding what is perceived as good and bad in the first place.

In other words, players are not completely deciding what is moral or immoral. The designers have already made a part of that judgment by declaring certain actions as good or bad, through different endings, the reactions by other non-player characters, and often quantified points on a morality scale (more on that later). For the most part, games clearly categorize what is "good" and "evil" (or "nice" and "aggressive"): Bioshock asks players to either “rescue” or “harvest” Little Sisters, and Mass Effect even goes as far as coloring paragon options as blue and renegade options as red. Players are merely deciding whether they agree with the game’s definition of what is moral and immoral, and then acting on their assessment.

In other words, players are not completely deciding what is moral or immoral. The designers have already made a part of that judgment by declaring certain actions as good or bad, through different endings, the reactions by other non-player characters, and often quantified points on a morality scale (more on that later). For the most part, games clearly categorize what is "good" and "evil" (or "nice" and "aggressive"): Bioshock asks players to either “rescue” or “harvest” Little Sisters, and Mass Effect even goes as far as coloring paragon options as blue and renegade options as red. Players are merely deciding whether they agree with the game’s definition of what is moral and immoral, and then acting on their assessment.

Some critics might see this neutral attitude on morality as a weakness, declaring games with these systems as being deficient in artistic voice as well as having a lack of moral fiber. Especially since most games have linear stories that are about the importance of life, freedom, and truth. They make it sound like games that allow players to perform heinous acts would lead them down the road of depravity. Participation in virtual murder for these critics is equivalent to actual murder.

On further inspection, though, moral choice engines can give the oft-criticized violence in games a moral compass, challenging sadism to circumstance. The media outrage against Modern Warfare 2’s controversial scenario, where the player can kill citizens in a Russian airport, but only as an undercover agent disguised as a terrorist, succumbs to the fallacy of attributing the player’s ability to do something with the game’s promotion of doing something. Then again, aggression and virtual murder without much justification is the most popular form of escapism and catharsis for players in video games with violence. Indeed, developers don’t need to give context to violence to be successful, but they must do so if they truly wish to be “mature”.

Phronesis

This impartial approach of morality systems also allows players to cultivate a skill Aristotle would call phronesis , defined generally as the ability to know how to achieve an end, and how to reflect upon and determine that end. In other words, it is the aptitude of being able to adapt to new situations quickly and to make decisions, given the context and the facts presented at that time, that fall in line with what the player desires to achieve. Normally, that context is survival, with the avatar’s life (or another character’s life) put in danger to heighten the effect and difference between selecting a good or evil action. In video games, players can explore the extremes of morality without repercussion in the real world.

This impartial approach of morality systems also allows players to cultivate a skill Aristotle would call phronesis , defined generally as the ability to know how to achieve an end, and how to reflect upon and determine that end. In other words, it is the aptitude of being able to adapt to new situations quickly and to make decisions, given the context and the facts presented at that time, that fall in line with what the player desires to achieve. Normally, that context is survival, with the avatar’s life (or another character’s life) put in danger to heighten the effect and difference between selecting a good or evil action. In video games, players can explore the extremes of morality without repercussion in the real world.

Just as in real life, no one is forced to obey a particular moral code, though society can provide a guiding hand, presenting various incentives to those who are compassionate (or aggressive) and selfless (or selfish) out of principle, a personality trait, or as simply a card that needs to be played in different situations as a matter of personal benefit.

Learning what morals are enforced, or not enforced, in a game becomes as integral as learning the game's rules and controls. It asks players to judge when to apply a rule and when to improvise, when to uphold the law and when to let things slide. In turn, they become wiser and more sensitive to real-world situations, learning how to navigate through and survive in a world rife with almost endless opposing ideals and beliefs. Participation without creed develops and scrutinizes the process of judgment – a readily practical skill that video games can impart on its players.

Free Will in Morality Systems?

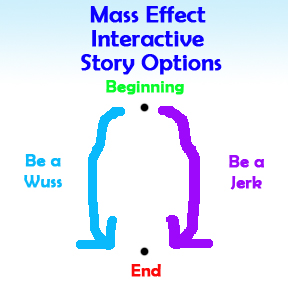

Modern Western RPGs have begun adopting morality systems as a way to add depth to the dialogue and extend the suspension of disbelief that the game doesn’t have fixed plot events. Games might boast “big decisions”, but they almost always have a central thread that serves as a pivot point around whatever branches in the story are given to the player, not to mention foldback schemes that seem to offer players a choice but ultimately lead them down the same path.

Modern Western RPGs have begun adopting morality systems as a way to add depth to the dialogue and extend the suspension of disbelief that the game doesn’t have fixed plot events. Games might boast “big decisions”, but they almost always have a central thread that serves as a pivot point around whatever branches in the story are given to the player, not to mention foldback schemes that seem to offer players a choice but ultimately lead them down the same path.

Though a player can choose to be paragon or renegade in Mass Effect, or gain positive or negative karma in Fallout 3, the story is still of a hero (or anti-hero) that saves the world through a specified series of story missions. At the end of the day, even the most widely branching games have preset endings and usually strict paths to get those endings.

The idea that morality systems provide players free will is only true if they are already bounded by pre-determined paths. This isn't to say that morality systems have been touted as the solution to the illusion of choice in video games. But to say that it will take decades of work in interactive video game storytelling before the consequences of a player's actions are not preset. Until then, morality systems are a good first step in that direction. Still, before this article becomes too pessimistic, the point is to have cut-scenes that react to the player choices meaningfully. (The debate on what is true interactivity or not can be made later.)

Points and Criticisms

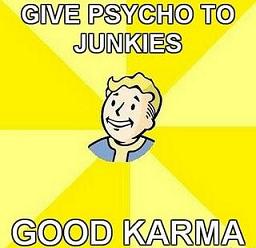

Another issue some critics have is in the quantification of morality, which they find dehumanizing because it ascribes seemingly lifeless numbers to the subjective, complex, humane subject of ethics. Earning, say, 3 “good” points for saving a dog’s life does sound arbitrary and foolishly appraised. But while mathematical expression is indeed a form of simplification, the numbers themselves don’t express quantity as much as they do variance of degree.

Our society does this all the time, like assigning a prison sentence of 25 years for first-degree murder versus 2.5 years for burglary. How many years in the sentence matters just as much as the relative difference between them, if just to illustrate what is worse by human definition. In the same way, games weigh various moral options as to their relative effect – rescuing thirty people from a burning building is a more selfless and reputable act than placing a piece of trash off the street into a trashcan. Of course, awarding a player 4,492,291 “good” points doesn’t make much sense, either – a scale, like the one in Fallout 3 which goes from -1000 to +1000, is much more practical.

Our society does this all the time, like assigning a prison sentence of 25 years for first-degree murder versus 2.5 years for burglary. How many years in the sentence matters just as much as the relative difference between them, if just to illustrate what is worse by human definition. In the same way, games weigh various moral options as to their relative effect – rescuing thirty people from a burning building is a more selfless and reputable act than placing a piece of trash off the street into a trashcan. Of course, awarding a player 4,492,291 “good” points doesn’t make much sense, either – a scale, like the one in Fallout 3 which goes from -1000 to +1000, is much more practical.

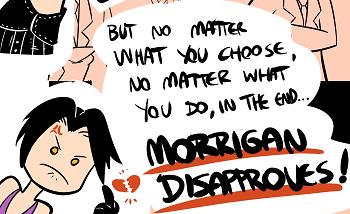

On the other hand, morality systems can be more profound and mature when there is no morality meter at all, and leave the dissenting eye between right and wrong to the player and other in-game characters. This allows the impact of a moral decision to depend not only on the player’s viewpoint, but also on that of the world of the game. In Dragon Age: Origins, each party member in the player's group can individually approve or disapprove of the player’s actions, which emphasizes the point that right and wrong is a matter of opinion and that the separation between the two is not always ideal.

When one party agrees, another will not. Saving an enemy’s life is generally seen as benevolent, but some party members and warring factions might see it as being too benevolent. The player might be able to influence others to perform or accept your deeds, but there will always be someone whose code of conduct (and who isn't just an enemy) conflicts with the player’s. Fallout 3 does this to an extent by not allowing the player to join with partners who perceive the player as being too good or evil for their tastes.

Solutions to a moral dilemma are rarely two-sided and should offer multiple alternatives that are neutral, impartial, or ethically grey. Not only that, but games need to give these alternatives as much weight as good and evil options. If only good or evil morality points unlock future dialogue choices or grant moral-specific powers, like chain lightning for being evil or area-wide banishing spells for being good, then why would players make neutral choices at all? There is one perk in Fallout 3 that awards a massive bonus to Speech for maintaining a neutral moral alignment, but this is an exception to the rule.

Solutions to a moral dilemma are rarely two-sided and should offer multiple alternatives that are neutral, impartial, or ethically grey. Not only that, but games need to give these alternatives as much weight as good and evil options. If only good or evil morality points unlock future dialogue choices or grant moral-specific powers, like chain lightning for being evil or area-wide banishing spells for being good, then why would players make neutral choices at all? There is one perk in Fallout 3 that awards a massive bonus to Speech for maintaining a neutral moral alignment, but this is an exception to the rule.

For morality systems to become more sophisticated, additional variables need to be explored to match the complexity of morality: (just to name a few) reputation (which will return in Fallout New Vegas), Jungian personality traits, different forms of justice (utilitarian, retributive, restorative), and the common exception of unconditional love. In this way, relationships between the player and in-game characters can become richer. Strangers that the player meets in the game might not know the player’s moral alignment beforehand. Giving the player the ability to hide their alignment through disguises or lies would create tension. Communities can have different laws, beliefs, and restrictions, compelling players to adopt, reject, ignore, or change the rules of those societies.

A Final Note

It’s easy to look at morality systems as that new hip trend, that gimmicky buzzword pervading games that are hot on the market. But despite their relative immaturity, they are the face of modern game design and indicate that the future of the industry is personal – whether through morality systems, motion-sensing technology, interactive stories, or exhaustive avatar customization creators. It reminds us that games have the unique potential to let its audience explore ideas without linear dictation and develop their ability to adapt to unfamiliar situations that challenge their preconceptions. Morality systems mark the advancement of video game storytelling and of the medium as an artform with unique, undeniable insights on the choices that make us human.