But is it art?

Let’s talk about art and accessibility! Trust me, by the time we’re done, you’ll have to read a game review at some point. [Skip about seven paragraphs ahead if you want to go straight into the meat of the review, though I recommend otherwise. ~Ed. Nick Tan]

Video games, still comparatively young to other forms of media, are experiencing a background transformation in that many self-described gamers probably don’t notice. Historically, in order to play a video game, one needed to purchase specialty hardware compatible with proprietary games purchased separately or go to an arcade to dump money into self-contained combinations of the two in an arcade. Also, in order to make a saleable video game, one needed significant amounts of money, relegating development and publishing to large, profit-driven companies.

This is becoming less true over time: free libraries are now stocking video games and consoles, relatively inexpensive or free development tools are readily accessible, and independent developers are actively finding ways to deliver cheap or free games that require little more than access to the internet on a wide(r) range of computers. Those last two points are significant in the elevation of video games as an art form, assuming we are considering video games to be art. For practicality’s sake, let’s do that for now.

The more artists we can invite to the video game table, the greater the range of art and expression we can expect. And the more accessible the art, the wider the audience will be. The fact is that mainstream gaming is often inaccessible due to significant costs and financial hurdles associated with purchasing hardware and games. The common face of gaming provokes a lot of discussion about price versus value, which leaves it as an art form mostly dictated by retail consumerism and capitalist economic structures. Take the buzz surrounding the technology in the Oculus Rift; virtual reality is exciting, but it’s also deflating for many people at $1,500 a pop.

When you delve into forms of accessibility when it comes to video games, money and technology seem paramount. They also are compounded further when it comes to physical and mental ability to play games—gamers living with various physical disabilities or forms of neurodivergence often must purchase additional peripherals and software to play games like others, for example. But if we’re going to discuss art, since video games are becoming more artful, we need to explore the idea of intellectual accessibility and interpretation, which I wrote about years ago.

I like to believe that many people have experienced a moment in time when they were exposed to art and didn’t “get it.” This has happened to me, someone with a degree in Art, many times and it continues to happen. The effect of that is different for everyone. For example, after you watch a confusing independent foreign film, you might trash it to anyone who asks.

Or sometimes society takes an ironic turn, such as with Andy Warhol’s prints of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup. A cursory Google search will deliver you tons of merchandise glamorizing what appear to be tributes painted in flashy colors. Many people, including those who buy this stuff, are unaware these reproductions Warhol printed were an effort to comment on and embrace commercialization and product accessibility. To them, they may just be flashy pictures, nothing more.

Art is subject to interpretation, and when the audience doesn’t understand the artist’s intent, no one is definitively wrong. When it comes to video games, the more developers try to stray from narrative, presentational, and gameplay norms, the more personal artistic expression players will be able to get from them. However, breaking convention also means disrupting consumability on a large scale. In other words, players are subject to reject games that don’t play like Super Mario Bros. or Call of Duty or have discernible, understandable narratives like Grand Theft Auto or Batman: Arkham Asylum. They might not “get it.”

That brings us to Cameron Kunzelman’s Epanalepsis—I had to look up the definition of the word, and Microsoft Word thinks it’s a typo. I am, of course, not faulting Kunzelman for picking such a title; it reminds me of when I was a teenager, looking up definitions to words in Fiona Apple and Alanis Morissette songs. But many players may not be interested in searching their dictionaries for words from the get-go. Just so we’re all on the same page, the title is not a machination in the vein of Edward Gorey. Its Wikipedia definition:

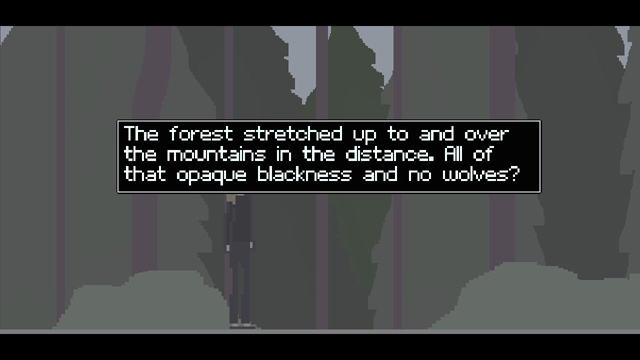

Here, you play as four characters over a 40-year period in what appears to be a science-fiction adventure game. I say “appears” because the adventure itself is short and arguable. The confusing plot, which involves time travel and folks trying to alter history, only gets interesting right before the game ends, 30 minutes after starting. You think it is just getting started, and it says, “The End.”

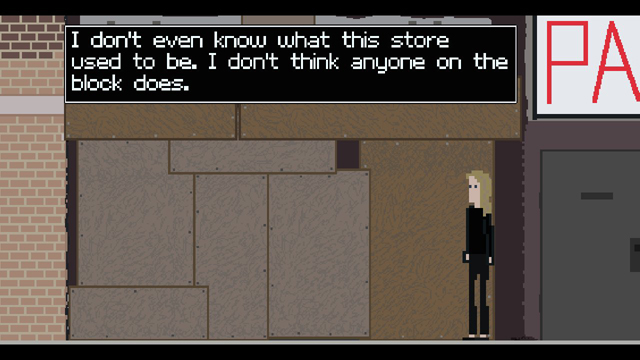

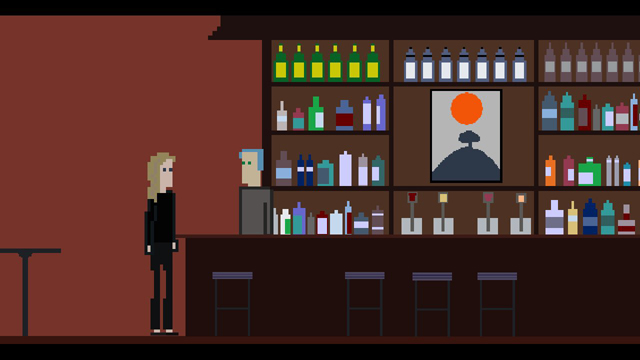

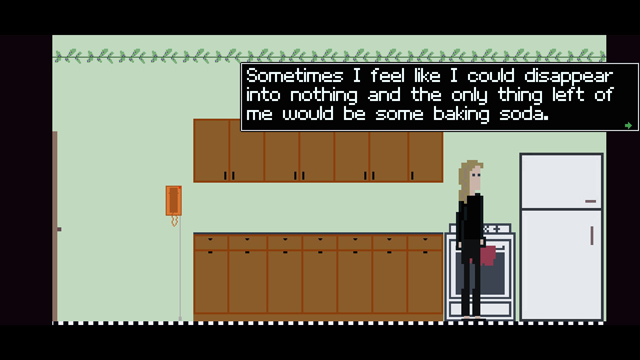

Well, this short period features Rachel, a young woman with little money and an interest in the local art scene; Anthony, a gamer and something of an elitist hipster; a robot charged with taking care of gamers in stasis pods, who gets wrapped up in a revolution; and one of those revolutionaries, only referred to as “INVENTOR.” Each character has minimal tasks to complete, which involve going from room to room and clicking on the objects or people mentioned.

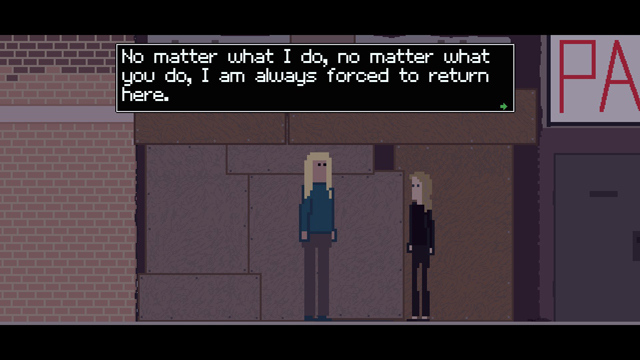

There is no inventory to manage, nor are there puzzles to solve. Complete the requisite amount of walking and clicking, and you’ll be shuffled along. Rachel, Anthony, and INVENTOR are each given choices, which are prompted by the time travelers, Pasus and Cascabel. These choices have little impact, affecting very little dialogue and marginally altering each ending, which is simply a description of what happened to each character. No matter what you do, you’ll play the same three chapters over the same amount of time with the same feeling that there’s less than half a game here.

Perhaps this is Kunzelman’s commentary on popular games, which present repetitive actions and illusions of choice with minimal significant impact. Those time travelers always describe the choices the playable characters have as if they’re fate and then lament about how they’ve witnessed the same disappointing outcomes each time. Rather than waste the player’s time for hours making a reflexive commentary, Epanalepsis distills the gaming experience into a short nugget, a single sitting. Then, in disbelief, you may feel compelled as I did to restart and see if the choices make any difference. They don’t.

If I do indeed get what comment is being made by Epanalepsis, I certainly don’t get the execution. It’s completely cynical and not engaging in the least. I’m trying honestly to follow a story that doesn’t want to be told, and I’m playing a game with accessible game mechanics of little value in the end. The cute pixel art graphics and moody soundtrack are a candy shell on a bitter pill to swallow: the feeling I could’ve imbibed the same insightful commentary through more engaging writing and mechanics.

Of course, there exists the possibility I just don’t get it at all. There’s nothing wrong with that, but either way, I have no interest in it. There’s a fine line that separates Merda d'artista and a can of crap, one which I’m not required to tread. All art is not for me, and I certainly don’t crave all art.

-

Cute pixel art graphics

-

Moody soundtrack

-

Story appears to be critical commentary on gaming conventions…

-

…but fails to be engaging or interesting.

-

Short length doesn’t work

Epanalepsis

-

Epanalepsis #1

-

Epanalepsis #2

-

Epanalepsis #3

-

Epanalepsis #4

-

Epanalepsis #5

-

Epanalepsis #6

-

Epanalepsis #7

-

Epanalepsis #8