The unforeseen problems of raising children.

Honestly, I never imagined that I’d return to This War of Mine again. Survival games already tie me up in knots, and the added layer of unending sadness that pervades the game wards me away like a curse. Yet curiosity got the better of me for The Little Ones, a console exclusive release and expansion, because of its inclusion of children. I couldn’t help but wonder how they add to the dynamic of rough survival in war-torn Pogoren. Unfortunately, it was the console adaption that I needed to worry about more than kids.

For those who are brand new to this IP, it’s a survival game set in a blockaded city during a war, specifically inspired by the events during the Bosnian War. With access to public utilities completely cut off, survivors are forced to forage for materials, medical supplies, and food during the night when the snipers can’t see them. When you start a new game, you’re given a large home and three or more survivors to look after in hopes of a ceasefire coming someday soon.

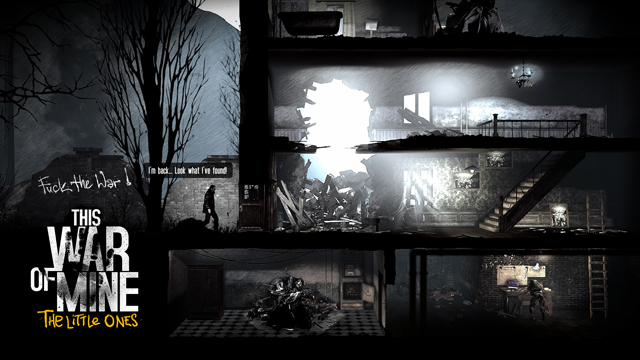

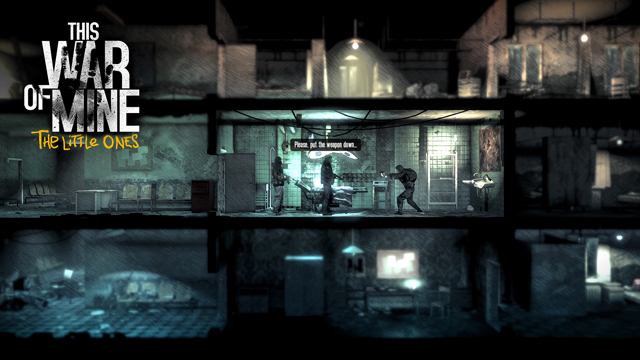

Your first day is spent exploring your new home for materials to begin building the tools you’ll need to last through the war and upcoming winter. And hopefully, you’ll find some food amidst the rubble. Your first of many nights is devoted to sending one survivor out to scavenge while the others guard the shelter. Some locations are easy to loot because they’ve been evacuated entirely, so they only require a shovel and some lockpicks. Others house other survivors of varying levels of aggression and willingness to trade. Or you may find soldiers armed to the teeth. The most valuable items are typically behind a lock, a defensive scavenger, or a shotgun, so you need to use stealth and strategy effectively to get what you need.

The daytime each day afterwards is spent building, cooking, eating, and tending to wounds or medicine. Occasionally, someone may knock on your door with items to trade or to ask a favor, such as patching a window in another shelter or giving medicine to a sick loved one. The people you steal from and trade with and your decisions with respect to these random neighborly visits affect the overall mood of your survivors, causing them to be content or sad, which affects healing and general will. Death of any survivor could cause the others to become broken, unwilling to move to save their own lives unless someone else is around to snap them out of it.

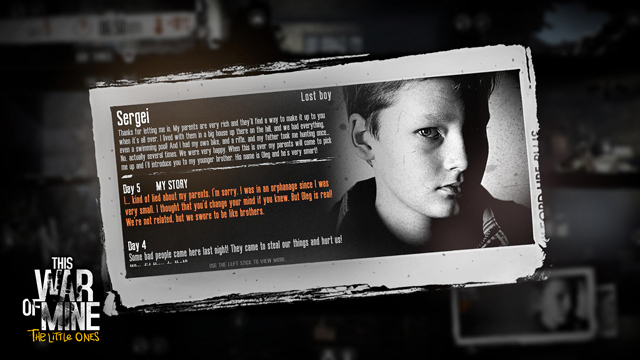

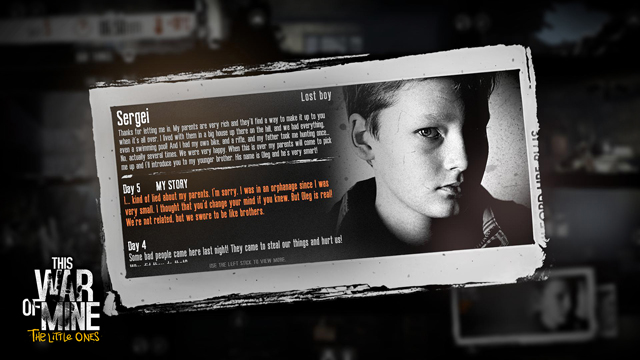

As somber an experience as it all is, I appreciated playing a game that basically offers no reward unless your residents manage to outlast the war. Children are another layer to the complex system of wartime survival, but they are a good one. I created my own campaign to include one from the outset, a boy named Misha, because the game’s pre-rolls kept giving me only adults. Misha, like any small boy, was spirited and had high hopes. Your job is to keep him that way, so it seems.

Initially, children can’t contribute. They won’t shovel piles of rubble, and they won’t build new workstations. But the other folks have the option of teaching children how to construct consumable resources, such as meals and cigarettes. Teaching, of course, takes longer than it normally would to make stuff alone, but aside from getting a more valuable resident out of the process, there’s something uplifting to the interaction. They have back and forth conversations that reveal the innocent ways children view the world even in dark times. For example, when told he’d be learning to capture animals, Misha asked if he’d be getting a gun or if they’d be trapping bears inside the home.

Children are also the only residents that can be spoken with during the day without being depressed or worse as a prerequisite. They are excited to see the scavenger come home and beg to accompany them the next time (which is not possible). When you’re out of resources to build things for the day, taking some time to play Rock, Paper, Scissors with a child will lift your mood even if it doesn’t do much for your characters. Meanwhile, children have interactions with the home and workstations that the adults do not. They can sit on tables and sing to themselves, draw on walls, or play hopscotch in a corner. Also, they can build small toys for themselves if scavengers come home with toy parts. They’re another mouth to feed, yes, but a valuable interruption to the cruelties of the ongoing situation.

However, an unforeseen cruelty is the gameplay for the console version—a disappointing exclusive, if you will. For all intents and purposes, the game is still functional, and one can work around the inconveniences, but having played the PC version, they are hard to swallow. For starters, in order to interact with anything in the house or within general view, players need to make the characters run very close to them. Whereas on the PC, I can click each survivor and set each on a task in a separate corner with ease, using the controller requires that I laboriously move survivors to their intended function while the others just stand around mindlessly. Actually, that’s not entirely true: Sometimes they’ll go find somewhere else to hang out, and in the case of a rambunctious child, that somewhere could be clear across the building from where you want them to be.

Once your character is at their chosen location, interaction can get super messy. They have the pick of any nearby interaction, but the game chooses one seemingly at random. The player must use the left and right buttons to choose the proper one, which can add frustration. After completing an interaction with an object that you wish to use again, the highlight will always move to another nearby object instead of staying put. Also, it’s tough to run to something you want to interact with and do so, and pushing the button absentmindedly leads to wasted time while your character does an about-face to use something else. Again, on the PC, interaction and movement is just a matter of precise clicking, and it’s much, much easier to multitask.

Compounding the marred experience was a persistent bug I encountered. I was on Day 13, and during the night I wished to re-visit a location, called Semi-Detached House, which I visited the day before, because I had items to trade. Yet no matter what I did, the game would crash every single time. Luckily, I could proceed by going anywhere else, but because your session is only saved at the beginning of each day, until I found the solution, I had to repeat the same routine of making fuel, cooking meals, eating meals, sending each character to sleep, upgrading my metal workshop, and playing with Misha. It was like Groundhog Day up in Pogoren. I’m glad I ultimately didn’t need to go back to the Semi-Detached House, but more than a week after release, I’m surprised to see this is still an issue.

It is disappointing to exert such caution when recommending This War of Mine:The Little Ones, especially to people who may not have a worthwhile gaming PC (low spec requirements notwithstanding), but the limitations of the port’s controls compel me to do so. For what it’s worth, this is still a good game, and the exclusive addition of the children survivors makes it a more compelling experience at that. But really, if you can play the PC edition instead, it’s easy to sacrifice all those kids for a much smoother experience.

-

Similar excellent concept as PC game

-

Children are a welcome addition to the experience

-

May need to make your own campaign to see them

-

Using a controller comes with severe limitations

-

Unfortunate bugs cause game to crash

-

Text readability may vary depending on size of TV and distance of player

This War of Mine - The Little Ones

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #1

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #2

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #3

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #4

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #5

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #6

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #7

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #8

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #9

-

This War of Mine - The Little Ones #10