He got a brain injury once. But then he outsmarted it.

[WARNING: This article contains copious, unmarked spoilers from Spec Ops: The Line, the HBO series The Pacific, the movie Vanilla Sky, and the movie/book Fight Club. Proceed at your own risk.]

You'll often see Spec Ops: The Line brought up in discussions about strong video game stories and narratives. In so reading, you might come across terrified comments about the game forcing players to shoot uniformed US soldiers, the fourth-wall moments that criticize the game's own genre, and the twist "The bad guy was you!" ending. While necessary inclusions, there's actually far more to Spec Ops: The Line than those factors. It's a brilliant example of games as art, with strength rooted in its mature, frightening look at Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The condition is so central to the game that we can't even talk about Spec Ops: The Line without talking about PTSD. The Line examines this topic with impressive power. The main character suffers from PTSD, but the player doesn't quite figure this out until several chapters into the story. Its extent isn't shown until near the end.

[Heath Writes a High School Essay] Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a severe mental health condition that can develop after a traumatic event such as rape, war, or a particularly devastating natural disaster. Nightmares and anxiety attacks are among its most common symptoms, though people suffering from PTSD may also have flashback-themed hallucinations or become easily addicted to a variety of stimulants and/or depressants.

In early days, before we knew much about the condition, different types of PTSD were lumped together and referred to as "Shell Shock," as airborne bombers made their way into warfare.[/High School Essay]

But PTSD is reserved for the fighters on the ground, right? Just the ones getting shot at and watching their friends die, right? We thought so for decades, but new evidence suggests that this affliction can reach further.

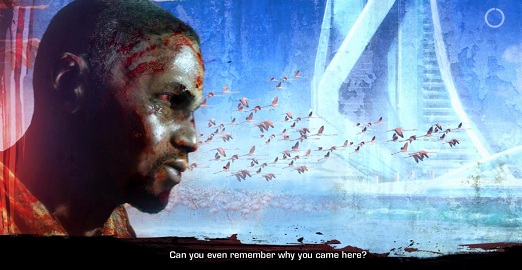

Above is Brandon Bryant, a very decorated former drone sensor operator for the United States Department of Defense. His job was to kill America's enemies from all the way across the ocean, with just the touch of a button. He had a literal kill switch. All he ever saw were zoomed-out, vague, low-res images on his screens, and, like many defenders of a nation, he was rarely told anything beyond "what you need to know." Press a button, fire a weapon, boom goes the dynamite, mission complete, call it a day.

Except that this gave him Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Odd as it sounds, yes, he got PTSD even being several time zones away from the action and viewing the events in sub-standard visual quality. Kind of like how the creator of Missile Command had horrifying nightmares about it.

Bryant's case proves that PTSD can happen without actually being in the war zone, and that's part of where Spec Ops: The Line becomes beautiful… in a horrible, terrifying, non-beautiful way. Spec Ops inflicts just a touch—just the slightest (and I mean slightest) taste—of PTSD on players. Because fuck you, players. I never liked you anyway.

It does this through design that aims not for Game of the Year awards, seven-digit sales figures, and dude-bro acclaim, but through design that makes the game downright uncomfortable to play. (Again, for emphasis, let me reiterate that it only barely scratches the surface of real PTSD. The feeling of this game sticks with us for an uncomfortably long time, but holds nothing on the stress and horror of war.)

PTSD affects the brain, and sadly, because of this, it's truly difficult to study and understand it. Without the doctor having the disorder, how can we know the validity of his/her conclusions? The bulk of a doctor's ability to do his/her job comes from education, sure, but would having been through colds, flu, migraines, bronchitis, and broken bones undoubtedly help on diagnose and treat such things? PTSD is a whole different story. When a patient tells a doctor "You don't understand," yeah, the patient is probably right. In that way, it's hard to call Walker, The Line's hero-gone-supervillain, a good guy or a bad guy.

The movie version of Fight Club shows us something similar, when the narrator (Edward Norton) realizes he and his friend Tyler (Brad Pitt) are the same person. Norton's character was suffering from insomnia, which he described as being "… never really asleep, but never really awake."

While PTSD and insomnia aren't the same, there are some similarities in the way they fatigue and confuse the conscious mind, sometimes rendering the victim unaware of what's going on around them and possibly altering reality. Fight Club's version of severe insomnia rewrites the narrator's memories; the film shows us replays of key scenes that have Brad Pitt completely removed. We see how they truly went down, but up to that point, the character had been convinced those moments happened in a different way.

This happens with PTSD. In my hometown, there was court case against an American soldier who had returned from the Middle East and barricaded his house and taken a family member as a hostage. He was going to blow the place up if "you sons of bitches" didn't leave the battlefield. Yeah. Turned out, his weapons were only a few firecrackers, but to him, they were weapons of mass destruction. He had a serious inability to separate reality from memories and imagination. (The man was thankfully found Not Guilty.)

Now consider all that went on in Spec Ops: The Line, we might not even know explicitly when or where Lugo and Adams died. And while we're shown the inconsistencies in the real story versus the way it's originally shown to players, there could easily be a hundred other things.

The most talked-about gutpunch in Spec Ops is the moment you realize you're fighting against uniformed American soldiers; the bad guys are also the good guys. You were sent here to kill "the terrorists" like any other military shooter, but here you are fighting your own countrymen (or at least your character's own).

The first time I had to kill American soldiers, it was a little bizarre, but I'll admit, I rolled with it because I told myself, "Well, it's just a video game." I got kind of a feeling in my gut like it was wrong, but was pretty sure it would go away like it did in Grand Theft Auto. Walking up to some guy on the street and shooting him in the head should not feel good. It should never seem like a good idea… and yet, in GTA, it does. We've become used to it.

The same holds true of war, in that the combatants often find ways to dehumanize their enemies, perhaps out of unconscious need. Commanding officers are much more likely to say "There are two targets on the tower." than the alternative "There are two men on the tower."

We call our opponents "hostiles" and "tangos" more often than anything. It's admittedly convenient, and the battlefield is no place for fine courtesy, but the reason behind it is that it simply makes it easier to kill other homo sapiens.

Wartime terms like "skinny" and "kraut" and 1,000 others can have racial and nationalist connotations at their cores, but the popularization of their use among military fighters served to make the enemies less human—to mask the fact that the opponent was another living, breathing person and make him seem just another… thing. An object. A target. This makes killing them much easier on the subconscious by taking away some of the potential guilt one might feel if one were to consider oneself a "murderer." [For a video game, the desensitization makes it "fun." ~Ed. Nick]

Spec Ops doesn't give us that safety net. Those "bad guys" are American citizens just like the main character, and the game will not let you forget it.

Reinforcing the magnitude of the situation through choices:

For a shooter with a linear story, the amount of choice in The Line is quite impressive. Even when the game seems to only be presenting the player with two choices, one can think outside the box and act independently far more often than one can in other shooters, or even most action games in general. The best part is that it doesn't always go out of its way to say "Press X to betray this guy" or whatever. You just have to do it. I was watching my wife play the part when you meet the the CIA guy the first time and she mused aloud to herself, "I wonder if I can shoot him?" It was hard to not say, "Yes, you can and it's so AWESOME because the game reacts to your choices and, and, and!"

The overall story takes the same general path and leads to a finite number of possible endings, but you have the power to alter key moments. Situations of such severity being tied to your actions makes you think things like, well…

PROFANITY or GET OUT OF MY HEAD:

Shit, this fucking game uses a hell of a fucking lot of profanity. Cockshit.

Some have called it overdone. Even my colleague and former construction worker Anthony Severino said that Spec Ops: The Line uses so much profanity that it started to make him a little uncomfortable. My wife and I noticed it, too—this game can swear with the best of 'em. Most military shooters throw out F-bombs and what have you, but Spec Ops crosses—excuse me—the line. This is intentional.

I suspect that the profanity was overdone because of the devs wanting to make you even more uncomfortable. I mean, most people who play that game—us included—don't care about "The F Word" and its underlings, but maybe they were overusing it to make us uncomfortable with something we usually brush off. Kind of like how we usually brush off shooting someone in the head, but they made it feel weird when the "enemies" were US Soldiers and harmless civilians.

There's also the fact that much of what you see is in Walker's head. Maybe with his condition, those words repeat themselves more often than they ought to? Again, we see the game afflicting players with mental stress.

Normally, I say that a game's inclusion of profanity doesn't make it "mature." It's true, the mere utterance of "fuck" and "shit" here and there might make a game something that can't be sold to children, but it doesn't make a game actually mature. Spec Ops: The Line's outright abuse of profanity does make it more mature, because all of it was for a reason. It's partially there because that's what a lot of real people would say in those situations, but more than that, the cursing is there to soak you in it. It's there to put you on edge during play and leave an impression afterward. And since Anthony and I readily brought it up in our discussion, I'd say it worked.

An Amazing Moment So Subtle, It's Even Overlooked When Praising This Game:

Ever seen Vanilla Sky (or Abre Los Ojos)? There's a moment when Penelope Cruz, in Tom Cruise's dream, starts quoting his best friend Jason Lee. Tom realizes, because of this, he's having a dream and just backs away. Backs away wanting to believe that this girl is real, but unable to deny the sad truth. And Penelope is just there like, "Yeah… I'm pretty much just a dream. Keep walkin'."

I got that same vibe when I looked back at the soldier who started saying his serial number as 867530- and then got cut off. When I first heard it, I thought maybe it was a joke by the devs to its older players who would get the "Jenny" reference. But then I thought about Vanilla Sky. It would then seem likely that this was one of Walker's hallucinations; the number could have been pulled from his memory. Since the fourth wall is broken so many times in the late going, it also seems probable that this number was chosen because millions of people can recite it easily.

Thinking about all of this also reminded me of one of The Pacific's last episodes after the soldiers came home. Eugene Sledge (an actual World War II vet, as most characters are in that show) goes bird hunting with his dad, and as he's carrying his rifle around in the woods, spontaneously freaks out, collapses in a fit, and starts crying. His father has to hold him and calm him down. Do you remember this? While Sledge is sitting on the lawn smoking a pipe in a later scene, his mother is shown growing concerned and a bit irritated with his state. His father then speaks some truth: "We don't know what men like him have been through."

And it's true. Unless you've actually been through a war, there will always be a certain inability to completely grasp what it's like. This, for the record, includes me. I previously shared a story of mine from 2008, about when I thought I was going to die from lack of oxygen. I'll go on record and admit that it's a sissy-ass thing to compare to fighting a war, but the point is, after that, I was an emotional wreck for a while. I'd just up and start crying for no reason—or sometimes with a reason, like the topic of suffocation being brought up. It was completely involuntary; tears just would start flowing on their own. Now, six years later, the "bad days" like that are extremely few. I consider myself lucky that this minor setback is the closest thing I've ever had to PTSD (because you can hardly call the two close).

But what if my touchiness on the subject of asphyxiation never went away? In Spec Ops, when the heavy themes and intentionally repetitive, grating gunplay begin to break you down and make you want to turn it off… what if you couldn't?

When you start feeling that urge to turn off Spec Ops: The Line, when you start to get too bored or too stressed or too tired out or whatever, imagine if doing so meant putting your life in danger. Imagine if you had no choice but to keep going. You have work in the morning? Fuck you, you don't have a job anymore, keep playing. You had plans with your boyfriend or girlfriend? Fuck you, learn to love the gun. Your family and friends are busy doing God-knows-what until you finish this shit up. And if you stray, if you let your guard down for two seconds? Boom, you're dead.

That's the feeling the game conveys more powerfully than perhaps any other. It's not intended to be a happy, fun, good-time experience that you get out with your buddies on the weekend, as confirmed by just how "meh" the online multiplayer mode is. That mode was obviously just put in there because no publisher will touch a shooter without such a mode these days, anyway. It seems to me that SO:TL was created as a work of art first and a video game second.

If made to play it again and again, on loop, with death as the consequence of failure or quitting, your candy ass would eventually break down and cry. Yet that's the kind of thing members of the modern military must endure. Developer Yager conveyed this in detail all too perfect with Spec Ops: The Line. Knowing full well that they'd receive comments like this:

…they still went ahead with inserting faulty aiming and repetitive design. Spec Ops: The Line is therefore one of the strongest examples of a game as art.

The genius use of game mechanics to strengthen a narrative, mature handling of such a serious topic as PTSD, and subtle criticisms of military shooting games put Spec Ops: The Line among the best games of the last generation.