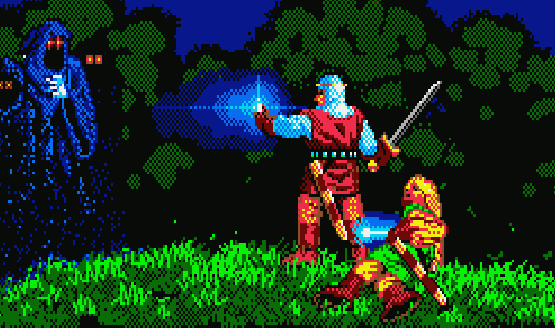

In order to celebrate 30 years since Ultima 5: Warriors of Destiny released on October 5, 1988, GameRevolution’s Tyler Treese takes a look back at how the incredible PC game is still impacting how role-playing games are made to this day.

When players reminisce about Richard Garriott’s Ultima series, they often talk about the seismic shift in tone that 1985’s Ultima 4: Quest of the Avatar introduced. Garriott, who was fed up with how so many of the players that bought his game were playing in a violent, evil manner in order to progress through the role-playing title as quickly as possible, decided to flip the entire genre on its head. There wasn’t an evil creature threatening to destroy the world that players had to defeat through raw power. Instead, the game focused on bettering oneself through eight defining principles: sacrifice, humility, honor, honesty, valor, spirituality, justice, and compassion.

It was one of the first games to really focus on the player’s actions, and still does a better job at demonstrating them than most current games do. It’s important to hammer home that everything the player did was thought to be good in Ultima 4, since it’s exactly what makes the twist in Warriors of Destiny so great. Ultima 5 took the morality discussion that its predecessor had started, and took an even more nuanced examination of it.

The Morality of Ultima 5

Rather than continuing to preach the same morals in a steadfast manner, Garriott made Ultima 5 a scathing look at absolutism. The ideals that were so present in Quest of the Avatar remained, but they had all been corrupted by Lord British’s replacement, Lord Blackthorn. The release can’t be separated from real-life politics, as its design reflected the current events that were happening in the late 80s. Outspoken evangelists would often appear on television to condemn others for certain acts, while they did the same in their private lives. Seemingly, all of the good that can come from philosophies and religion was being corrupted by humanity’s greed and their constant desire for more.

Further complicating things is that the entire basis upon the government in Ultima 5 is built upon what the player did in the previous game. Lord Blackthorn greatly admires the ideals that the Avatar set forth during Quest of the Avatar. So much so, that his absolute rule has a strict code of honor and laws. If anyone is caught lying, they’re liable to quite literally lose their tongue, and those that don’t give generously to charity must be completely broke. It’s a philosophy built upon taking good ideas and then twisting them over the edge.

It would be understating Ultima 5‘s many complexities to act as if its exploration of morality was all the story had. Also featured is a fantastically written redemption arc that showcases the power of change, be it from good to bad or vice-versa. However, its many technical achievements are just as impressive as the writing that made the story so memorable, and to ignore their impact on the genre since then would be just as criminal.

Warriors of Destiny was one of the first RPGs to have a complicated time-of-day system that would change the world rather than just make the sun go down. The residents of Brittania had their own daily routine, and it helped the fantasy setting feel all the more as if it was living. While this feature has become commonplace today, it was practically unheard of in 1988. It’s exactly what Nintendo used to make The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask such a thrilling adventure, and complex day and night systems were still being used as a key selling point for games nearly two decades after it was implemented in Ultima 5.

In an August 1994 interview with Computer Gaming World, Richard Garriott claimed that Ultima 5: Warriors of Destiny was his favorite of the classic RPGs he had made. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. Not only is its interesting way of tackling morals still relevant, it’s shockingly prescient to look back upon when people in power are actively trying to overstep their boundaries out of a sense of moral righteousness.

Further showing how far ahead of his time Garriott’s design was, is how Ultima 5 ends its adventure. The Avatar finally returns to his own time after saving the kingdom. He’s not greeted with a reward for his good actions, but rather he returns home to find that his house was robbed of every valuable possession he had. It’s not the most subtle allegory, but it’s a scathing metacommentary that evil doesn’t just exist in the past. This type of commentary on real-world society was rare back then but is increasingly seen in modern games, with the likes of The Witness and The Path of Motus using it to their advantage. This goes to show that even 30 years after the fact, the DNA of Ultima 5: Warriors of Destiny can still be seen all over gaming.