Nazis suck and it’s a shame that that still needs to be said as Nazism and fascistic thinking still infects the world even 76 years after the Second World War. The physical war may have ended but the idealistic battle lives on as bad actors continue to weaponize ignorance, ignore past atrocities, and ready the world for more suffering. Fiction can help remind people of inhumane crimes and Paradise Lost is an intriguing adventure game poised to do just that but from a shorter point of view.

A pre-teen’s post-apocalyptic journey

Paradise Lost stars Szymon, a 12-year-old boy drawn to an abandoned Nazi bunker in Poland to fulfill a personal goal. These underground Nazi hideouts — inspired by real mysterious Nazi bunkers in Lower Silesia, Poland — were meant to hide the Third Reich from the nukes they set off in a desperate attempt to hold back the opposition. But their absence allows Szymon to observe how these evil forces functioned in a way not unlike how the player explores Rapture in Bioshock. Decrepit, destroyed, and dark, but with a story to tell.

Darker stories usually set the stage for adult protagonists, but the contrast here is the narrative and gameplay hook. Szymon is not B.J. Blazkowicz so it would not make sense to put him in a typical first-person shooter where he’d shoot these dang Nazis. Szymon is better suited to explore their bunkers, not blow them up. Game Direction Bogdan Graczyk explained the narrative justification for a young protagonist as a way for the team to experiment with scale and more clearly demonstrate the large moral gap between children and such a cruel regime.

“It’s interesting to investigate how it would feel to play a first-person game with a different perspective with a smaller protagonist where everything seems bigger,” he said. “And you don’t have all of the capabilities of an adult person. You have to be a bit more sneaky with how you traverse this world.”

“We also felt that on one hand, it’s a deeply personal story of Szymon but on the other hand it’s a very, very epic story of a great conflict of huge proportions. So we felt that a younger and more innocent protagonist leaves a wider space for interpretation and emotions for the player.”

Lead Producer Chris Panas-Galloway spoke about that gap in a more straightforward manner as this perspective allows players to “reflect on the sins of adults throughout history and show the damage caused by those to the younger generations.” Stepping into smaller shoes with fresher eyeballs makes it easier to empathize with the powerlessness children feel during war as their world is so forcefully shaped by the grown-ups.

Poetic ties

The young dealing with the sins of the old also ties into the game’s title that has been borrowed from John Milton’s 17th-century poem. The exact parallels are not quite clear yet, but Graczyk says that both pieces of media are about history repeating itself and how future generations deal with what came before. Panas-Galloway, again, was more straightforward in saying that both are about good and evil, but the game also finds some gray area to dabble in.

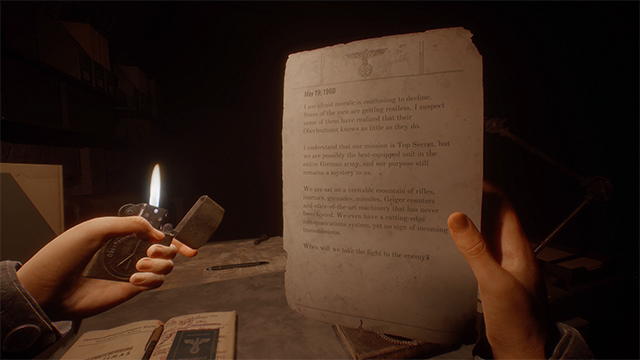

Wandering through the underground quarters as a tourist lets the player dig deeper into these war crimes by reading notes, listening to audio logs, and observing the environment around them. PolyAmorous looked at games like Gone Home for inspiration as that 2013 title is a prime example of letting the players piece together what happened through supplemental collectibles. Paradise Lost has a lot in common with that game since both are essentially walking simulators with some light puzzle-solving and heavy player-driven worldbuilding.

Finding gray area in a black-and-white conflict

Some levels are not focused squarely on the Nazis as one of the game’s middle chapters is centered around a civilian facility that became overtaken by Polish rebels. The story collectibles in this area are more about the rebel occupants as they struggle for survival in a depressing building meant to mimic an apartment complex, but with only around 10% of the soul.

Instead of dealing with the Nazis, their internal struggles are laid bare by each note as they bicker about survival and who should call the shots. These documents seemed to demonstrate the aforementioned gray areas as cults and Nazi science presented many ethical quandaries the Polish had to deal with.

Digging through the drama is just one of the game’s many promising layers. Szymon’s story is the central pillar, but that mystery unfolds alongside a few others. Players will also find answers to what happened in this abandoned bunker as well as the story behind Eva, one of the game’s few other living characters. She communicates with Szymon through a radio and their relationship builds from there.

If that sounds a lot like Firewatch, it is. Graczyk and Panas-Galloway both gushed about Campo Santo’s well-received walkie-talkie-heavy walk-and-talker and how it excelled at creating an emotional bond between physically distant characters. Paradise Lost doesn’t seem to have as much back-and-forth communication, but that addition injects more life into the world and creates more for the player to unfold and examine. She, along with some parts of the story, can even react to the player’s actions.

All of these narrative threads are naturally intriguing given their inherent secrecy and Panas-Galloway said having each narrative plotline organically fold into each other is part of the game’s special sauce.

“The story expands from a personal story to a story of Eva as well and the motivation to help Eva or not or while you’re going through Szymon’s search,” he said. “And then additionally, the secrets of the bunker and what happened there and adds that extra layer of intrigue. It all comes together at the end.”

Remembering the sins of the past

And while the story within the game seems important, it’s also clear that it’s still drawing from a twisted ideology we still see far too much of. PolyAmorous’ Polish roots give the team a different lens to see the game in because Poland is still scarred from Nazi attacks that happened over a half-century prior. History is harder to forget when the reminders are still there. Graczyk spoke openly about these constant reminders and how games like this can maybe — just maybe — help keep these atrocities in the open so that humanity can’t forget its past sins, especially as fascism still continues to rear its ugly head in the United States and across Europe.

“I think it is always a good idea to remind people of the horrors of the twentieth century and of the Second World War and the totalitarian crimes,” he said. “Alternative history is one way to do this. It gives you a sense of freshness and a bit more freedom. We’re a studio based in Warsaw and Warsaw was one of the most destroyed cities in the Second World War. We can feel the atmosphere and see the evidence of the Second World War everywhere around us.

“I see the rise of all the fascism as procured by ignorance so maybe just reminding people constantly of the atrocities of the Second World War, maybe it can open their eyes that the threat is real and we’ve already done some pretty horrible stuff to one another as human beings.”

Paradise Lost has a lot riding on its heavy narrative as it is a narrative-heavy game. It doesn’t exactly have dual-wielding gunplay to make up for any story-related slack so it will live or die depending on how well it tells and paces out its tale. But its multifaceted, alternate history premise with a healthy amount of personal and environmental intrigue gives this story a great deal amount of promise, meaning PolyAmorous’ first game could be quite a memorable one.