Brains…(loading)…Brains…(loading)…Brains!

It never fails. You’re about halfway through any Resident

Evil game, you go through

a big steel door, the music starts pounding and a particularly brutal zombie

looms before you. I really respect these ambitious

zombies – they’ve usually strapped on a couple extra arms, perhaps

a big tentacle or a giant eyeball, maybe even a skinless crocodile head where

a leg used to be.

But these fearsome, overachieving

zombies always overlook some fatal flaw. They’ll foolishly be standing over a vat of acid on a narrow catwalk that some pesky S.T.A.R.S. agent can shoot out from under them. Or they let themselves get too close to the suspiciously placed, potentially explosive barrels of oil, and then it’s goodbye undead, hello real dead.

This,

of course, is just my marginally clever way of introducing you to Resident

Evil: Outbreak, an ambitious game that – like our zombie friends – spends

so much time adding cool new appendages that it forgets to check for nearby vats

of acid and easily gets lured into giant trash compactors.

But before we get into what’s wrong, let’s stare deely into that giant eyeball

and find out about the great new stuff in Outbreak.

At long last, Outbreak finally gets rid of those tiresome S.T.A.R.S. agents, putting you instead in the civilian shoes of one of eight ordinary people. These delicious brains are all gathered in J’s bar late one night when the T-virus first infests Raccoon City. Things are clearly going badly outside, and you only have a minute to get your bearings before zombies start smashing their way into the bar.

You can choose your character based on your play style, since each one has unique

special items and abilities. For example, the reporter Alyssa has some skill

at lock picking and can open containers and door that nobody else can. Yoko,

a student, has a backpack doubles her potential inventory, an important bonus

in a game with tiny inventories. Plumber David carries a toolbox, useful for

repairing broken items and modifying weapons. Ah, the magic of duct tape.

The controls have been changed to the less precise but more intuitive objective-directional

controls like Capcom’s Devil

May Cry series (of course, none of these regular Joes can move like Dante). It makes Outbreak easier to navigate, but also a bit harder to aim and shoot.

However, no matter whom you choose to control, you’ll play through a series of five long, loosely connected chapters. There is less story here than in other Resident

Evil games, but if you don’t mind missing out on the ubiquitous details of yet another Umbrella conspiracy, the excellent cutscene movies more than make up for it.

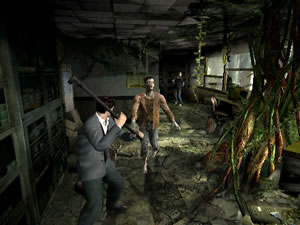

The in-game graphics are almost as good, with only a few muddy background textures

to occasionally mar the view. The 3D environments look great, the characters

move smoothly and the zombies shamble menacingly. The environment is far more

detailed than in previous Resident Evil games, but Outbreak pays dearly for

this eye candy.

Outbreak is

Outbreak is

plagued with long, frequent loading times. Bad ones. Sometimes as long as 20

seconds, which seems like forever when you’re being chased by zombies and intensity

is immediately followed by impatient frustration. The areas are pretty small,

so you’ll have this problem a lot; sometimes it seems as if you spend as much

time waiting as you do playing. The game recommends using the PS2 hard drive,

which cuts the loading times about in half, but no console game should rely so

heavily on a $100 upgrade.

Speaking of which, to really appreciate Outbreak you’ll also need the $40 network adapter because this is the first online Resident

Evil game. The game is nearly identical whether playing online or alone, the only difference being that the humans who help you out are controlled by the computer in the single-player game and by actual living humans in the multiplayer version. It functions much like LOTR:

Return of the King; your advancement in the multiplayer has no bearing on your single-player saved game. That also means you can hop online and play levels you have yet to unlock in the single-player. Online is clearly the way to go, since when the computer controls your companions, they’re only slightly smarter than a zombie.

You can play with up to four players trying to survive the zombie menace. This leads to some of the game’s greatest moments, where you and the other survivors barely make it through an area. The last two of you make it through the door; you’ve selflessly risked your life picking up a fallen friend, using your shoulder to help them, half stumbling, to safety. Another teammate quickly begins nailing boards over the door to block off the attacking undead while the last one stands guard, just in case. It just feels like a classic zombie moment.

Too bad you can’t really share that moment with those friends, because in a giant oversight,

Capcom did not include voice-support in the game. All you can do is use the right

analog stick to say one of eight things, like “Yes,” “No,” or “Come

on.” (In the single-player game, your friends will spout these comments endlessly

and randomly.) So you end up saying “Thanks!” when what you really need to say

is “Oh my god, that was close! Awesome job guys. Alyssa, come over here and pick

this lock, would you?” Even USB keyboard support would have been nice, but no

such luck.

The rest of the sound is great, setting a truly scary mood. Zombie groans and

The rest of the sound is great, setting a truly scary mood. Zombie groans and

mysterious bumps in the night become terrifying in the infected city. The perfect

music fleshes it all out in a crescendo of madness, until you’re brought back

to earth by Resident Evil‘s traditionally laughable voice-acting.

Even so, Outbreak is filled with lots of great little improvements.

The zombies can smell blood, so if you’re bleeding they will come after you,

even from other areas. The game has a ton of unlockables: new weapons, outfits,

art, and other stuff to keep you playing again and again. And if one of your

party members succumbs to the T-Virus, you better have some bullets left because

they’ll start coming after your brain next.

However, Outbreak tries to do so many cool things, it tends

to lose focus and falls flat on its face over a couple major issues. In order

to really play Outbreak properly, you need the hard drive and

the network adapter, which totals an extra $140 – incidentally, only ten bucks

less than the cost of an Xbox. A better plan would have been to make Outbreak for

the Xbox in the first place, which already has a hard drive, a network adapter,

and built in voice-support.

The good parts of Outbreak are so good, it will keep fans (including

me) playing despite the problems. Unfortunately, the game is

too ambitious for its own good and too top-heavy for the system for which it’s

exclusively designed. A zombie could have a hundred flailing tentacles and a

cool set of giant spider legs, but without

a mouth, it just hasn’t got any bite.

-

Zombies!

-

Good sound and graphics

-

Lots of neat little features

-

Online co-op play

-

Marred by lack of communication

-

Needs the hard drive to run smoothly

-

Longí¢â‚¬Â¦ Loadí¢â‚¬Â¦ Timesí¢â‚¬Â¦

-

Reallyí¢â‚¬Â¦ Reallyí¢â‚¬Â¦ Longí¢â‚¬Â¦