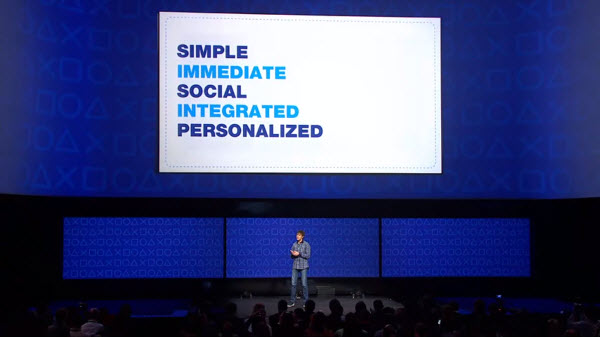

Personalization has a price. Throughout the PlayStation Meeting 2013, Sony's representatives keyed in on "personalization" as one of the main facets behind the development of the PlayStation 4. It seems like a benign, a thoroughly positive concept—that a company considers the preferences of its users and then tailors the user interface in the form of relevant searches and recommendations. The system learns your behavior, your likes and dislikes, and offers advertisements and products that fall within your general comfort zone.

However, "personalization" is also a buzzword that hides what is, from one perspective, information control. By the act of an invisible algorithm, information filters in and out based on what it thinks you want to see, for the sake of showing us content that we would be most likely purchase. If you principally play, say, Call of Duty and Killzone, your home page might be filled with first-person shooters, whereas an RPG aficionado like myself might have more Bethesda and BioWare videos and DLC offers. My home page will most likely look completely different than yours, and you probably wouldn't know it unless you saw my home page in the first place.

It's an uncanny marketing function that's user-defined, but not user-controlled. Without consulting you, information that you might care about can be filtered out without you ever knowing. Besides, you can't miss what you've never had. Based on your "likes" and common search keywords, these algorithmic gatekeepers can create what Eli Pariser calls filter bubbles that distort your gaming world from those of others.

If you're wondering why nothing fresh seems to be thrown your way, personalization is a part of the reason why. These filter bubbles are reinforced, a kind of self-fulfilling continuous loop. If you tend to select news and offers about first-person shooters most of the time, the filter automatically increases the rate at which you see more news and offers on first-person shooters. In the pursuit of companies wanting to keep our attention and entertain us the most, it doesn't show you games that you might normally find uninteresting, uncomfortable, or challenging to your usual play.

This passive impact of personalization, though difficult to measure, results in a sharper division between gamers. The concept of a well-rounded gamer becomes further out of reach, with gamers holed into specific types rather than being encouraged to seek out new genres and less popular, though critically successful, titles. It presents a gaming world that feeds into your confirmation bias, into your compulsions and instant stimulation rather than your interest in exploring something new and innovative.

Without Mario Tennis and Mario Golf, I would have never cared about the sports genre. Without Bioshock, I would have never cared about first-person shooters. Though I might not care much about the Halo franchise, that doesn't mean I don't wish to watch the Halo live action trailers. Would "personalization" have prevented me from experiencing them? Now luckily, I'm a game critic who is privileged to be bombarded by a wealth of different games all of time. But most gamers are not lucky enough to afford or experience all these titles, especially if they don't see them in the first place.

Hopefully, the obsession for relevance and personalization will not undermine the lofty pursuit of gamer cosmopolitanism. This can happen as long as developers balance personalization by providing visibility to games that are important, critically successful, and out of our respective filter bubbles. So would giving gamers a slider or checkboxes that control how deeply personalized our user interfaces are. Gaming should be a world of possibilities, not a personalized echo chamber.