I expected the last GDC talk I attended, entitled “Designing for Free: How Free-to-Play Games Blur the Line Between Design and Business", to be a snoozefest. The description talked about how designing for free-to-play means having to think about business decisions as a part of making design decisions; I expected a panel of social gaming experts talking about the most profitable way to monetize an in-game item or ways to turn a profit on paid stat boosts.

What I didn’t expect was a heated debate with designers yelling across the table about the moral imperative of contemporary game design. These guys totally got into it, and I almost expected Matt Worch (Dead Space 2) to throw a chair at Ben Cousins (Battlefield Heroes) towards the end of the panel.

Moderator Tom Chick (actor and game journalist) frontloaded the debate by talking about how he felt monetization had ruined several of his favorite games, Lord of the Rings Online and League of Legends, and then challenged his “free-mium” panelists (whom he each identified with the status of a religious icon) to justify these kind of design choices. He asked what they could do to keep from losing players like him.

Cousins, whom Chick introduced as “The Devil Incarnate” for his frank and earnest promotion of the free-to-play model, was unapologetic. He called Chick’s departure from these games as “churning out” and that a certain number of users would churn out, but that these players weren’t profitable for the company anyways. He did, however, throw Chick a bone by saying that 99% of free-to-play games implement their free-to-play model crudely, and were not doing it right.

Soren Johnson (Dragon Age Legends), whom Chick introduced as a “Fallen Angel", mentioned at some point that players would necessarily have to become payers for the model to work. David Edery (Triple Town, Realm of the Mad God), or Chick’s “Misguided Saint", was much more combative, claiming that our idealization of the recent era of games was a mistake; the pay-for-play model of the arcades was much more cutthroat, our era of heavy DLC and DRM was inevitable, and that free-to-play is much less invasive than advertising for “sugar water".

Cousins added later in the conversation that the annoyance over having to deal with being sold something in-game was at least equal to the annoyance of going to a store and dropping $60. It was then that Matt Worch entered the conversation, saying that he was trying to figure out a way to get into free-to-play if he could find a way to make it work.

Worch was almost like Chick’s secret weapon in the war on free-to-play games. His arguments against the movement weren’t based on aesthetics, like Chick’s, but on scientifically backed ethics–he cited studies that children who displayed a capacity for delayed gratification did better educationally and had greater emotional intelligence later in life. His argument against the free-to-play model was that it played directly against this by offering instant gratification by monetizing success.

Chick jumped in and commented that the free-to-play space thrives on “Whales”–players who buy everything available for sale–and questions whether free-to-play takes unfair advantage of these individuals. Edery was particularly feisty on that, saying that those people, if the game weren’t there for them to be addicted to, they’d be addicted to something else, finally pronouncing, “That person is fucked!” Cousins compared it to a hobby; I extrapolate that he meant this in the sense that Warhammer 40K is a hobby that quickly separates a hobbyist from all their money.

Worch also confronted the free-mium game makers with his concerns that he wanted to make games that were about more than just making money, games that teach something about the human condition, though he didn’t know if that was possible. Cousins and Edery attempted to assuage his fears mostly in the Q&A. Cousins promoted his idea of Monetization 3.0 (1.0 being customization for, say, horse armor, and 2.0 being the current "built-in suck model"), which is based on existing Korean and Japanese models where players have an emotionally positive response while paying for services.

Worch responded by challenging them on questions of game balance. If you give players better materials or increased levels for pay, how could the game remain fair? This was where Edery and Cousins were finally able to reach across the table to Worch. Cousins again pointed towards there having to be an emotionally positive experience in taking advantage of a monetized service.

Edery talked about implementing “Excitegrades” instead of upgrades. He cited his game Realm of the Mad God, where instead of giving the player a better bow, you let the player buy a shinier bow that fires one third as frequently but does three times as much damage, keeping the game in balance. The shinier object becomes a desirable social status symbol but doesn’t break the game.

It says something about the way the wind is blowing, that when Edery pronounced that paid games would be killed by free-to-play–and Johnson stated that the $60 game model might collapse–no one argued, not even Worch. Everyone on the panel seemed to have already accepted that idea as inevitable.

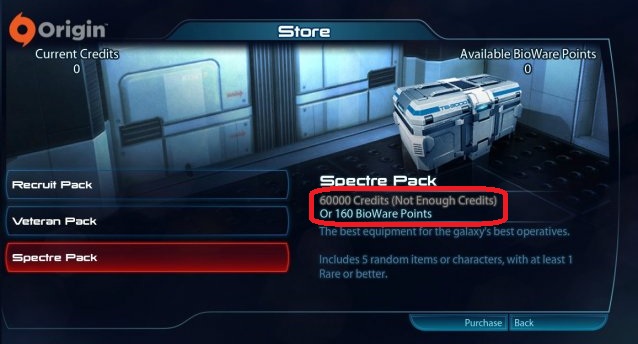

Chick pointed out that it’s happening in the triple-A space; Mass Effect 3’s multiplayer is already using the same monetization of temporary power-ups as a free-to-play model. Soren Johnson likened the shift to the industry adoption of 3D, implying that the single-payer model for games would be like 2D gaming, and might thrive with smaller teams of designers making truly innovative games.

After all, Cousins reasoned, publishers had only pushed people to make great games because they sold. All that free-to-play games did for designers-turned-publishers was make their former publishers’ motivations more readily transparent. At the end of the day, everyone has to get paid.