Every year at Blizzcon, fans fill the halls of the Anaheim Convention Center to celebrate their love of all things Blizzard. Whether it is meeting up with guildmates, getting a first peek at new gameplay content or making awkward conversations with cosplayers, attendees come to Orange County every year to revel in Blizzard’s intellectual properties. However, none of those things have drawn me in quite as much as the Darkmoon Faire, the dimly lit corner of the convention where fans sacrifice their wallets to the altars of merchandise.

On the surface, the Darkmoon Faire is a place where people can buy and trade pins and figurines. Every year marks a new series of pins, each with a gold variant that can be purchased in a blind box. The figurines are also sold in a blind box. This year, Blizzard added badges and backpack hangers into the mix. All with varying levels of rarity, all of them sold via blind boxes. Blizzard has perfected the art of the loot box, wielding the strength of their IPs with the kind of nuance and sneakiness that would make a rogue blush. However, in their quest to dominate every attendee’s bank account and living room, a fascinating side effect occurs: for two days, this tiny corner of the convention hall develops its own market economy.

Also: Moira Overwatch Release Date is “Coming Soon”: New Hero Announced at BlizzCon 2017

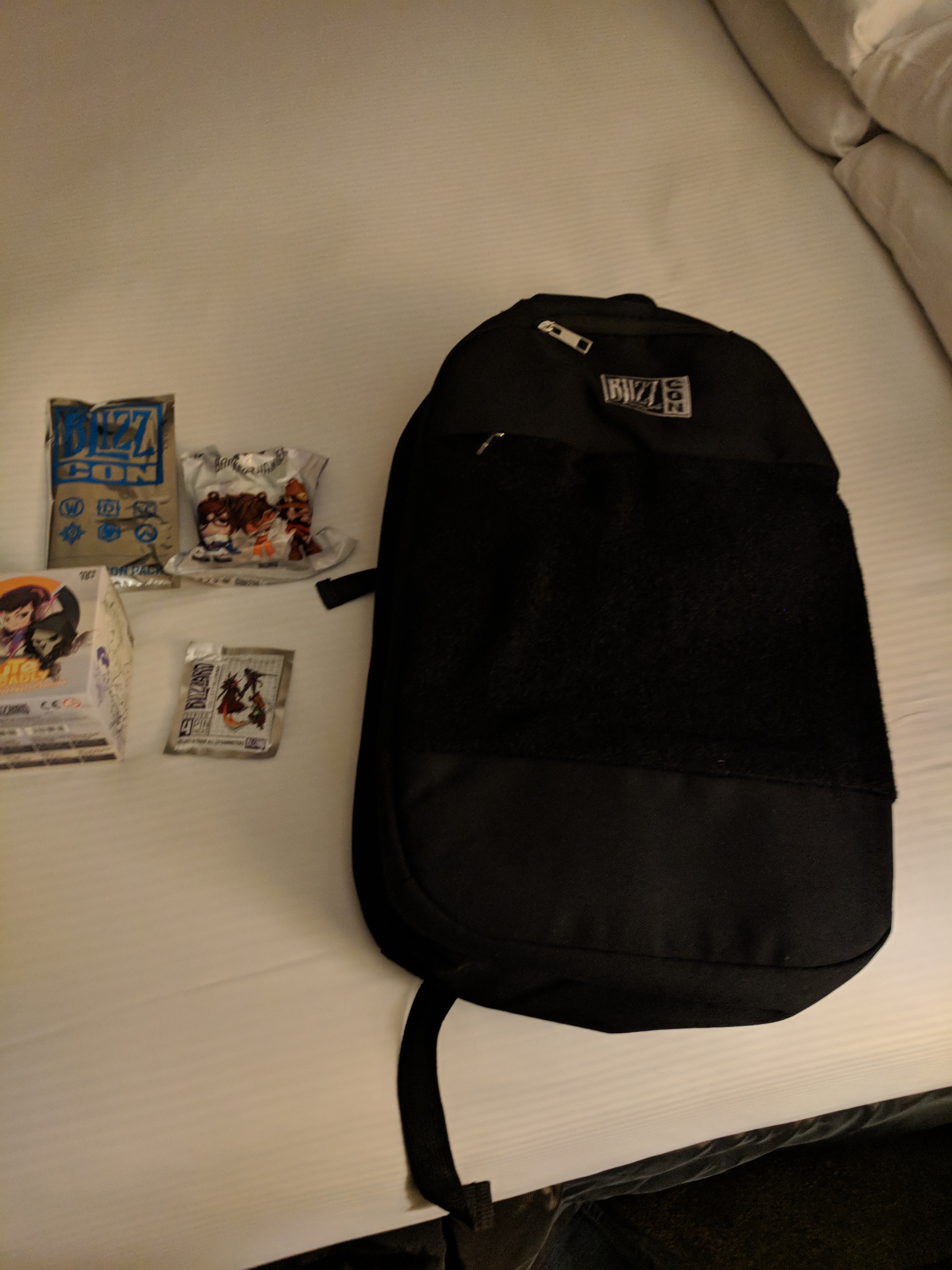

This year, every Blizzcon attendee received a random pin and figurine as part of their goody bag; my bag contained a Mercy pin and a D.Va figurine. With absolutely no knowledge of their worth, I made my way to the farthest corner of the convention center, the Darkmoon Faire, to find out.

Supply and demand ebbs and flows in the Darkmoon Faire. Amazon and eBay are no use in these parts, partly because of the spotty Wi-Fi but also because the market is so localized. Without anything to measure an object’s value (other than the price of additional blind boxes), word of mouth becomes your only source of measuring worth. I was going to have to chat up a few strangers, get a feel for the room. I squeezed my way to the trading tables, a small grouping of picnic benches and narrow bar stools behind the pin shop.

Just by looking at the collections on display, I could see there was an unspoken hierarchy to each table arrangement. The serious pin traders took up most, if not all of the picnic benches. Their large black binders left little room for anything other than Serious Business. The smaller, higher bar stools were for the figurine enthusiasts, or those looking to trade what little they brought with them. Many others spent their time wandering, stopping only to ask others if they were willing to trade.

I spent the first hour or so as one of those wanderers, looking like a lost child as I tried to get my bearings. Figurines, if not my specialty, were at the very least my field of interest. As I struggled to gauge the value of the D.Va I had in my hand, I ended up trading it for a Sombra. A trade I would quickly regret, as I learned soon after that D.Va was actually very high in demand.

Most people were reluctant to tell you an item’s demand unless you already knew. I mean, why would they? In the pin/figurine/badge/backpack hanger game, getting what you want means having more information than the person you’re trading with. People sensed a scarcity of D.Va figurines, which in turn drove up demand. I doubt Blizzard had created an artificial scarcity of D.Va figurines (no odds are printed on the box, so it can only be presumed that each figurine in the set was produced equally), but this market was driven by instinct, not hard numbers.

There was one figurine that was more sought after than the D.Va, however. Printed on the box was a “mystery figurine” that manifested as a shadowy variant of the Reaper figurine. Here was an item from which all other trade values were based. For the rest of my day, I made it my goal to acquire this figure. Which, all told, took me about half an hour to get.

Every pin, every figurine, every randomized tchotchke that Blizzard sold carried a perceived value. A value not only assigned by the market, but by every individual participating in it. Many people simply enjoyed the social aspects of trading. Others were looking for something more specific, and would not budge until they got what they wanted. Every figurine I held in my hand as I traded my way to that Reaper figurine shifted in value, depending on who I traded with. I was able to acquire a second figurine by trading a pin I did not want for a figurine they did not want. That second figurine, coupled with a newly reacquired D.Va, got me the shadowy Reaper. Once I acquired the Reaper, I thought to myself, I wonder how much this is worth in cash? Cash is, after all, the real (ish) gold standard.

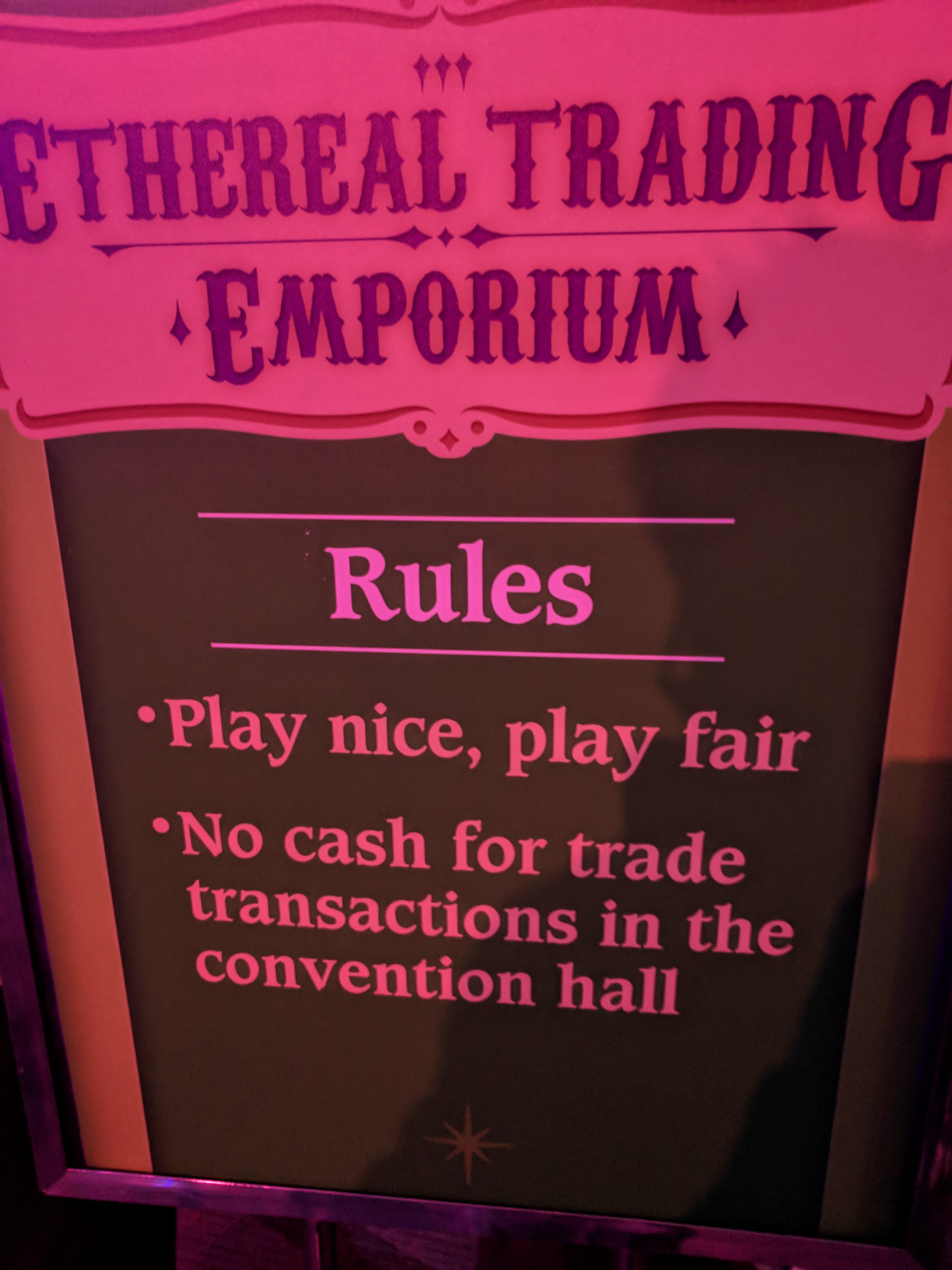

I hesitated to call Darkmoon Faire’s trading halls a free market economy based on one simple rule: no cash trades were allowed on the convention floor. In previous years, I had watched as people made hundreds of dollars buying and reselling pins and figurines. One man told me he paid for his whole trip every year doing that. These people took perceived value to their absolute capitalistic conclusion: what is this worth in cash? Every person I traded with this year, even those I knew who dealt in cash trades, were hesitant to say the c-word. Word got around quick that those who tried to sell their items were immediately kicked out of the convention, their badges confiscated. I heard whispers, too, that those seeking cash for their wares should look outside the convention halls, but my snooping dug up no leads.

As the day wound to a close, I held in my hands what I thought to be the most valuable figurine at this year’s Blizzcon. After all, I had traded two figurines just for this one. But now that the show was over, and people were packing up their things and leaving, what value did it have left for me?

A nice little souvenir, I guess.