Kris Ruff, a writer and narrative designer at developer Klei, recently went on Twitter to coin a new phrase: “empathy degradation.” It is, to paraphrase her explanation, a condition found only in interactive stories such as video games and exists when the playtime starts to negatively affect the narrative flow of the game. It’s an interesting point that helps explain how the interactivity of the medium can sometimes make us stop caring about some aspects after multiple hours.

Ruff’s example of the phenomenon is spot on. A blacksmith greets the player each time with the voice line: “What can I do for you today?” The first time you hear that it sounds like a reasonable thing a blacksmith, or anybody working in retail, might say to a customer. The third time you hear it in exactly the same voice and cadence, it might feel a little disingenuous. By the tenth time, that blacksmith is no longer feels like a person but an interaction point.

The longer you play the game, the more your empathy for its characters and immersion in its world begins to degrade. Even in Red Dead Redemption 2, which arguably has the most living world available in any interactive media, still decays as players spend more time in the game. This is because, as Ruff describes it, there is only so much authored content that can exist in a game.

These are the things that the game developers have scripted and added to the game, and it is a finite resource that feeds the players ways to empathize with characters and willingness to believe in that world. Once the game has run out of new scripted content and begins to repeat itself to the player, this empathy and illusion begins to degrade. The random events in Red Dead 2 might at first make the world feel alive, but after you’ve seen your seventh stranger kicked in the head by his horse, the impact is lost, so to speak, and the world and characters in it feel less real. But while this new term can help identify one of the causes that stop you from immersing yourself in a game, it is far from the only reason.

More than just playtime

Empathy degradation explains how narrative hiccups can negatively impact the immersion of a game through its characters and script, but the gameplay itself can also break down the mirage. While the overall playtime erodes the player’s empathy for the game’s characters, playing through familiar territory has the same effect on the game’s world. As another Twitter user describes it, D-Day has been a common level found in countless World War II games, but the repeated use of the level, iconography, and design has desensitized seasoned players to the experience. This isn’t empathy degradation as coined by Ruff, but another factor that can disassociate players from the game.

But it doesn’t always have to be a repeating script or similar levels that break the immersion for the player, although these are strong influences. While time will always be a factor, some mechanics and conditions in certain games can, unfortunately, erode the immersion that the player wants to have for the game world. It’s mostly in games that have a strong narrative focus that the player wants to immerse themselves in. The Council, which released episodically throughout 2018, is a great example of the many ways in which the player’s immersion can be broken.

As The Council begins, even players without an interest in history are caught up by the setting and story that surrounds them. There is a tantalizing mystery, several interesting characters, and a strong gameplay mechanic to keep the everyone engaged.

But as they are forced to walk the same overly long corridors again and again, the immersion begins to falter as repetition sinks in similarly to the D-Day example but throughout the same game. Like so many other games that have the players backtrack through previously completed or explored sections, this can immediately detach the player from the carefully constructed universe. And as players lose interest in the world, they also lose any emotional resonance with it. But in The Council, there is another cardinal sin that breaks the experience for the player: the central character’s motives and actions being impossible to understand.

Belief in the world

When playing any narrative driven game, nothing breaks the illusion as quickly as the central character acting in a way that the player can’t understand or relate to. That isn’t to say that all characters have to think and act exactly like you, but they do have to operate in a way that you can understand and empathize with. The final scenes in The Last of Us had players debating whether or not Joel was in the right, but no one suggested it wasn’t in character.

We’ve all played a game where we’ve not been given the dialogue option we want. Maybe we’ve worked out who the traitor is or have witnessed an event that demands an explanation, only to find that the script hasn’t changed and we can’t act in what we think is an appropriate manner. As soon as that happens, the simulation is rendered false in the player’s eyes and restoring any willingness to suspend disbelief is a real challenge.

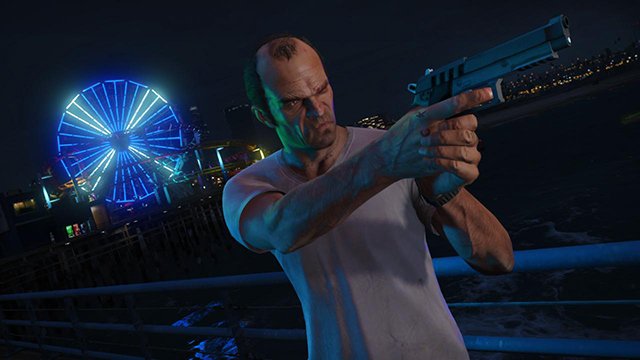

Other games erode the illusion in different ways. While Grand Theft Auto 5 and Red Dead Redemption 2 might have hundreds of hours of authored content, the gameplay mechanics and loops will still slowly degrade the player’s empathy with the characters and belief in the world over time, even if they haven’t reached the end of the scripted content. In GTA5, for example, players will have frequent and violent run-ins with the law. Over a couple of hours, it’s safe to say that hundreds of police officers will be killed, with the player suffering very little consequences. There is never a shortage of police officers to kill and maim, and the way that they chase fugitives is unbelievable and video gamey, which is fine for purely interactive, mechanical standard but not as much for a deeper, more introspective meeting.

Empathy degradation and these other aspects of games that break immersion are not something that can be so easily found in non-interactive media. The worlds depicted in books, television, and film are much smaller than the ones found in games, and the authored content encompasses everything available to the audience. You cannot pause the story in a book to explore the town it is based in, or wander down the wrong corridor to see what is there. And the central character not acting on something that the audience knows isn’t unreasonable, because that character is not an avatar for the audience. In essence, other mediums don’t repeat themselves in the same way video games do and can’t dull watchers in the same way.

And this means that we haven’t had to think these terms until recently when game narratives started becoming exponentially more thoughtful. But now that we have games with stories and deeper worlds that players want to immerse themselves in, we will have to start looking at ways of tackling this newfound problem with interactive storytelling. Player agency is great for a lot of different reasons but does open up the medium to empathy degradation and immersion breaking incidents, even in the most enjoyable games.