GDC isn't like E3, PAX, or other more highly commercial-oriented shows. So it's something of a surprise when a piece of hardware or software takes on a big draw at the conference. Last year when I had the chance to ask game devs what they were seeing, they were dashing off to see World of Tanks, with its addictive play in manageable short play sessions. This year it was the Oculus Rift.

The Oculus, a virtual reality display that can track head movements and translate them into the game, is one of the toasts of the conference and definitely one of the things to see… if you were willing to wait 2+ hours to get to it. The unit shown on the GDC show floor isn't the final version, but is instead a dev kit that Oculus VR will be sending out to its Kickstarter funders and game developers. Even so, it's incredible.

Jesse Schell, of Schell Games, famous for his DICE 2010 talk on gamification in the future, mentioned the Oculus as one area he also saw in the future of gaming at his GDC talk on Game Narratives, as a way of being able to engage in a more immersive world, which would probably come in the PC space. Valve is already supporting it in Team Fortress 2 with a dedicated VR mode that shipped last week on Steam and four different experimental control schemes.

In a talk about the device, the company founder, Palmer Luckey, likened it to the next evolutionary step in gaming, like the development of the printing press for books and the development of color and sound in movies. He believes that it will make it possible for us to experience more subtle and interesting game narratives because of the heightened realism of the VR experience.

Luckey's VR experience comes from medical simulations of surgeries, military simulations, and psychological fields where VR is used to assist people with confronting fears and PTSD, and he spoke to other uses of the tech, like Formula One's advanced simulations with cars on hydraulic systems to simulate inertia and momentum. In a follow-up at the end of the talk, he touted gaming as the ideal place to push the tech, because gamers are early tech adopters who care about authentic experiences more than public opinion.

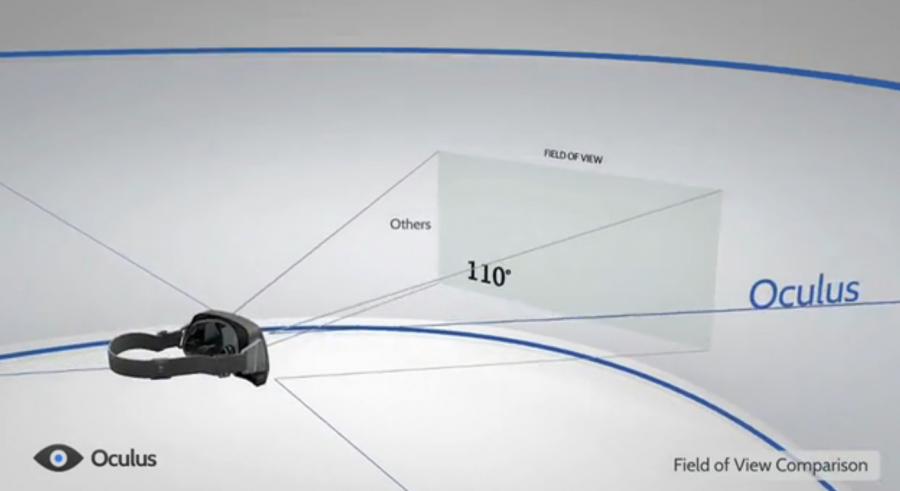

The Valve developer, Joe Ludwig, who spoke about working with the VR tech, didn't dispute the claim. In their talk about lessons they learned from translating Team Fortress 2 to VR, they praised it over other VR systems. they tested for its wider field of vision (more on that in a moment) and spoke as if this level of VR integration was a fait accompli—the future being developed today.

After waiting for two hours in line—thank you, Fire Emblem, for staving off the boredom—got a chance to try the device. The Oculus was set up on a dev version of Hawken, which I was also experiencing for the first time. The GDC Oculus techs told us to look for “the sweet spot” when putting on the device, and then strap into it.

The Oculus Rift dev glasses give you a full range of vision and in the demo put you into the cockpit of the Hawken mech. At the techs' suggestion I turned around to look behind me and saw the seatback and metal frame of the cockpit, with the view tracking my head movements. Then he spawned some bots for me to shoot at.

However, for the first time in years, first-person shooter controls were no longer intuitive: The targeting reticule wasn't where I was looking, but instead at the front of my cockpit which I had to turn with a thumbstick instead of my head. Valve dev Ludwig said this was a problem for them too, and that controls were something the industry developers at their talk would have to develop. It made targeting more difficult, but perhaps because it was more realistic; in real life, people don't shoot automatically in the direction that they're looking—they have to aim. One solution for this that's been suggested is motion control interfaces specifically for aiming.

The view itself is amazing and frustrating at the same time. The Oculus Rift isn't like strapping on a pair of 3D glasses at a movie—the VR unit shows a video feed that stretches like an individual IMAX screen for each eye, filling the entire field of vision. The Valve tech praised the Rift as being better than other VR tech because it matched the whole field of vision, while other VR system don't even have peripheral vision. This makes the view much more natural than any video game display you've likely ever seen in the way it handles motion and movement in the frame.

Still, it's frustrating. Due to the limitations of the tech, the dev kit displays information at 640×800 pixels for each eye. That means that you have only 640 pixels (less than a Standard Definition television's 720) to cover the entire horizontal visual range for each eye. This makes it so that the image is only distinct in a central cone of vision, which Ludwig said was about 500 square pixels. Outside of that cone, it's a bit of a blurry mess; the Oculus Rift has a severe myopia problem.

While it might be easy to look at an iPhone or iPad and wonder why this is so, the Oculus Rift is strapped directly to the face, just scant centimeters from the eyes. It requires the use of precise lenses that have to be calibrated for the individual user to see the images. Add more tech or more complex lenses, and you increase the weight, making it harder to play and wear. However, Luckey said, as hardware solutions present themselves many of these problems will be solved and some will have been made for the dev kit devices currently shipping (currently the Rift is also a wired device, due to issues of power and latency).

Still, the device is incredibly impressive. One of the things the techs had people do in the demo was fly the Hawken mech as far above the level as possible, and then drop, while looking down all the way, to a crash against the concrete. As the machine fell faster and faster, and finally reached terminal velocity, my stomach turned and I experienced vertigo, something I've never felt from a video game.

The Valve devs talked fairly extensively about ways to combat the problem of motion sickness. One surefire way to create it was to change the angle of the head against the player's wishes. This caused motion sickness because the view didn't match the person's inner ear adjustments. The company's founder talked briefly about a unit that could artificially stimulate the inner ear to create the illusion of the head-tilting, but mentioned these units were hardly ideal, least of all because they involved sending a strong blast of electricity threw a person's head.

Similarly, the realism in visual motion, even if the system is currently lacking in resolution fidelity, meant that people had problems playing faster player classes. The scout, for instance, runs far too fast (20 miles per hour, according to Ludvig, but more like 40 according to Oculus Rift creator, Luckey) and that the rocket jump made people particularly nauseous, because they had to look down to perform the action and saw the ground rush away at an accelerated rate (something most people aren't used to).

After playing Hawken for a few minutes, I began to get the hang of it. Jumping, flying, and then dropping while firing were accompanied by a straight-up adrenaline rush and butterflies in the stomach that I wouldn't have believed was real before I strapped on the glasses. To put it simply, it felt more real and scarier. Targeting in the game was difficult because of the low resolution, HUDs have been discouraged for game developers (for the moment, though, the device's creator expects resolution to quickly get better as they move forward), and all firing was blind.

The Valve developers' solution for this for TF2 was to paint the reticule on the side of the target itself, so it would change distance, like a true laser sight that paints a dot on the side of the target. This solves a general problem with 3D targeting that those who played Resistance 3 in 3D may have encountered. In Resistance 3, in order to line up the iron sights properly you had to shut one eye, just like in real life; however, this proved more annoying than immersive in that game.

Regardless of the developer learning curve and the current limitations of the resolution, the Oculus Rift is an amazing piece of tech that feels at the very least like the future of 3D gaming, providing an experience you can't get anywhere else. It almost makes me sad I didn't get in on it when the Kickstarter was up, so I could get my hands on a dev kit to play those early VR-ready games sure to be developed by the people in the full giant hall for the Valve talk, almost all of whom raised their hands when asked if they'd either pre-ordered or were getting the Rift dev kit from Kickstarter.

Blurry? Sure. Can it cause eyestrain if not calibrated correctly? Yeah. Does it need new control schemes and best practices? Indubitably. But I absolutely see a future for a whole new kind of game development, one where everything will feel just that much more real, even without the work they are already doing on those issues. The Oculus Rift was like seeing the future through beer goggles.