***SPOILER ALERT!!***

Shame on me for not playing BioShock Infinite until this past weekend. I can blame the game for releasing on the same week as GDC 2013, but I must admit that I've been caught in a replay of Final Fantasy VII… which in hindsight is serendipitously about the mind filling in the gaps with false memories. Is Cloud Strife simply Booker DeWitt in the multiverse of possibilities? Yes, those are the kind of analytical questions I posed after finishing BioShock Infinite. (My mind goes into mysterious places.)

At least I have revealed the self-deception of why I didn't pick up BioShock Infinite until this past wee… wait, no, I've done this before. I must be stuck in a time loop. That's what I get for spending the whole day analyzing BioShock Infinite and then spending the whole night spitting it out in pages of words that I now shall reveal. A lot better than using hundreds of Voxophones, I bet.

Also check out Daniel Bischoff's review of BioShock Infinite and the BioShock Roundtable podcast with Daniel, Alex Osborn, and Jonathan Leack!

What The Hell Just Happened?

Long story short, Bioshock Infinite's story revolves around the creation of a time paradox. Once Elizabeth gains the ability to see across the entire probability spectrum, after Booker directs Songbird to destroy the giant siphon hidden inside the gigantic angel statue, she realizes that the only way to eliminate Zachary Hale Comstock is to remove him not just from their timeline, but from all timelines.

This is tricky, however, since Comstock is merely Booker DeWitt if he had accepted the baptism more than twenty years ago. Eliminating Comstock by shooting him the face in every time-space one by one in the infinite set of possibilities where he exists would not be feasible.

To truly eliminate him from existence and break the cage of fatalism with her newfound power of free will, Elizabeth must use her power to go back in time to the point before Booker approaches the priest for the baptism and ensure that there's no chance that he would accept it. Thus, Elizabeth (and all instances of Elizabeth across the probability spectrum) drowns Booker, who willingly accepts this solution, so that he would never become Comstock.

This creates a time paradox, because Elizabeth can only exist if Comstock exists, as he is the one who purchases Elizabeth/Anna from Booker. But if all instances of Comstock are removed, then how can Elizabeth exist in the first place and murder Booker in the past? The fabric of time cannot exist with this paradox, naturally causing it to reset and choose the path of least resistance in which all timelines can run smoothly. This is done by turning the baptism from a variable ("accept" or "refuse") into a constant with only a single option ("refuse").

Since Booker now always refuses the baptism, Comstock is never born, Columbia never exists, Booker never gives Anna away, and Elizabeth never exists, which is why the instances of Elizabeth disappear one by one after she drowns Booker in the water. Nonetheless, Anna probably still exists as we see that Booker awakens in the post-credit scene on October 8, 1893, the date when she was most likely given away. This is inferred from various Voxophones timestamped October 15, 1893 by the Lutece twins and the fact that Lady Comstock falsely gives birth to Elizabeth in only seven days.

What happens after the post-credits ending scene is completely up to the imagination of the player.

The Lutece "Twins"

Of course, there are more characters who are central to the twisted layers of the story, and none are as important as the Lutece twins, Rosalind and Robert. Some might argue that they might be more pivotal to the story than Booker and Elizabeth, since they are the ones attempting to restore the balance of time. Well, at least Robert does, because as Rosalind says in a Voxophone, he feels guilty purchasing the baby from Booker in the alternate timeline and wishes to set things right. Rosalind is a fatalist too, who in the rowboat objects "to the entire thought experiment." While Robert is a nihilist ("…where he see a blank page, [Rosalind] sees King Lear"), he believes his cause is just and he thankfully follows through.

Eventually, Rosalind comes around to her sibling's side after Fink sabotages their contraption and scatters the pair across the possibility spectrum. They attempt to nudge the possibilities like a Groundhog Day experiment, as much as they can at least since their power is faint compared to Elizabeth's eventual godlike sight and since their involvement might alert Comstock to their presence, to work out all of the variables that lead Booker and Elizabeth to the time paradox explained earlier.

During one cutscene in which the pair has Booker flip a coin (heads or tails), which explains the concept of a constant across time-space, it can be noted that the chalkboard Robert wears already has 122 marks on it (there are 100 marks on the other side). This implies that this is their 123rd attempt to set things right and that the Booker the player controls is the 123rd instance of Booker they've tried. In the rowboat, Robert responds to Rosalind's "He doesn't row?!" with "No, he doesn't row," implying that he's tried the scenario where Booker rows the boat and it ends in failure.

Indeed, Robert's redemption rests on guiding Booker through his own journey of redemption, and it's likely that the Lutece twins killed the lighthouse guard ("The Only Obstacle" is written on a picture on a desk inside the lighthouse) in this effort. Curiously, Booker must also ring 1-2-2 at the lighthouse in the opening cutscene to unlock the rocket that leads him to Columbia. If we count from 0-0-0, 1-2-2 would be the 123rd number in the series. I don't believe this is mere coincidence.

It must also be remarked that Rosalind Lutece is sacrificing herself, perhaps begrudgingly, and that Robert Lutece is sacrificing Rosalind. Somehow, Booker accepting the baptism always makes the Lutece sibling Rosalind (or is it the other way around in "the chicken or the egg" kind of way?) while him rejecting the baptism makes the Lutece sibling Robert. So if the time paradox works as intended, all instances of Rosalind must also perish since Booker would then always reject the baptism. But perhaps she is already content with this fate as she feels complete with Robert at her side. Then again, this is entirely conjecture considering that we do not know what happens to the twins after the credits roll.

(Quick aside: If the twins do it, would it simply be masturbation? Hmm…)

On Baptisms

Since the ultimate solution of the time paradox centers around Booker's refusal of the baptism, many players will likely view BioShock Infinite in an anti-religious light. Some flat-out disagree with this notion, believing that the story's message is more about the corrupt use of religion as a false cure for past sins rather than about a judgment on religion itself. As Alex Osborn points out in his feature on being a religious person and a video game player, this issue can be difficult to handle.

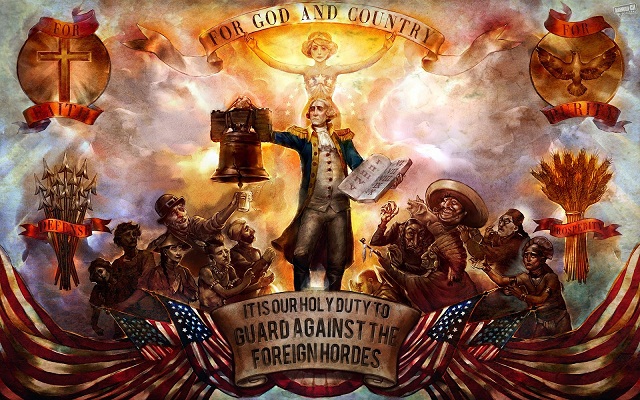

I agree and disagree with the anti-religious interpretation of Bioshock Infinite. On one hand, there would be no point for using baptism, mentioning the Lord multiple times, turning Lady Comstock into a figure similar to the Virgin Mary, and calling Elizabeth the Miracle Child if the developers at Irrational Games had nothing to say on the subject of religion. Comstock bluntly uses religious doctrine and aspects of Christian mythology to create cover stories that mask his crimes of deceit, racism, and genocide.

On the other hand, the underlying theme of Bioshock Infinite that ties the story together is not about religion as much as it is about running away from the truth and attempting to seek false redemption by burrowing into an external solution that doesn't solve the root of the problem. Booker and Comstock, albeit in different ways, are both unable to face the sins of killing innocent people as a staff sergeant at Wounded Knee and as a hired hand of Pinkerton.

Accepting the baptism turns Booker into Comstock, an antagonist who abuses the modern conservative notions of national pride and religion by mutating them into extreme ideals and justifications for his past deeds. In one Voxophone, Comstock asks, "[Does] the one left behind in the baptismal water… exist in some other world, alive, with sin intact?", which cheekily references Booker but also shows that he doesn't see himself as a sinner. It's no wonder that he freely distorts American exceptionalism, white supremacy, and golden calves in the shape of the statues of America's Founding Fathers into a well-constructed defense of one colossal lie.

Meanwhile, rejecting the baptism turns Booker into a regretful veteran who believes he has become irredeemable, succumbing to alcoholism, gambling, and general despondency, a (literally) bleak gray world where his self-worth becomes so low that he sells Anna to Robert Lutece. It's not until the rescue attempt in the alleyway that he realizes his grievous mistake, but it's too little too late.

Regardless of the baptism and its outcome, Booker fails to reconcile his sins peacefully. He is not emotionally prepared nor spiritually ready for the journey of redemption, and so the baptism is doomed before it even begins. For an analogy, it's like a murderer who finds Jesus only to kill more people in his name; he obviously did not get the message.

In other words, BioShock Infinite does not flat-out reject religion insomuch as it asserts that religion cannot fix a broken man who chooses to remain broken. In fact, it's a formula that can lead to the ruination of man himself.

Booker's Inner Journey

The character progression of Booker DeWitt could have been made less subtle and thereby more believable throughout the story, but the components exist under the scrutiny of observation. At the very least, BioShock Infinite doesn't hit players over the head with a heartfelt message to make a point.

Booker's character arc rests on his coming to terms with the realization that Comstock is fundamentally a part of him. He both is and is not Comstock. Even if he bashes Comstock's head and drowns him in the baptismal water, it doesn't erase the sinful acts of their shared past. Killing Comstock is not the absolute end Booker (nor the player) hopes it was. In fact, for the final battle sequence Booker symbolically replaces Comstock but in a different image, in a role reversal where he must protect the ship by commanding the Songbird and eliminating the Vox Populi resistance who might as well make no distinction between Comstock and this apparent "imposter" of Booker DeWitt.

The concept of facing oneself can be reflected in the use of mirrors, or lack thereof. It's curious that there are no mirrors anywhere, notably in bathrooms where one would expect multiple mirrors to be placed. Only the opening sequence has a mirror near the entrance of the lighthouse, where a plaque asks Booker to cleanse himself before reaching the supposed heaven that is Columbia. Perhaps this mirror is merely a way for the player to see what Booker looks like, as this is a first-person shooter, or perhaps it's just an graphical oversight, but I believe the absence of mirrors after that scene is intentional. Both Booker and Comstock cannot see themselves for who they really are, which is the underlying theme that fuels the story in the first place.

Each level of Columbia is designed for Booker to destroy the layers of lies Comstock has built around himself, and thereby simultaneously and ironically, Booker's lies as well. Monument Island represents Booker's neglect of his daughter, tucking Anna away in a room while he wallows in despair. Here he must confront the lie that he was merely keeping Anna safe from harm, notably from himself. In the Hall of Heroes, Booker must eliminate any notions of national pride and necessity as justification for his actions at Wounded Knee. The facade of the opening levels of Columbia begins to crumble.

In Fink Industries, he revisits the oppression he enforced as a Pinkerton, probably also against black and Irish workers. Here the lie is that he only did this because it was his job. Booker in an alternate timeline states in a Voxophone: "It's one thing to hurt someone because you need to; it's another thing to enjoy it." While this certainly takes a jab at the player who is probably enjoying the death cries of foes getting blasted by plasmids and bullets, it also describes the Vox Populi and its leader Daisy Fitzroy.

The oppression they've suffered has become a rationalization for the excessive violence they commit in their protest. Both Daisy, who smothers herself in Fink's blood, and the alternate Booker, who becomes a propagandized martyr who has as much influence on the people as Comstock does as a prophet, die for their actions. It's just another example of how Booker is Comstock merely flipped on his head. But also, in this manner, BioShock Infinite does not take a side on the debate between conservatism and liberalism by showing how both extremes can lead to equally dangerous and inhumane outcomes.

By the ending, Booker peels off each lie of self-deception until he discovers that his own mind fabricated memories when he entered Comstock's timeline. As Robert Lutece says, the mind fills in the gaps as necessary, even if they are white lies that help Booker push through Columbia. Despite the drone-like repetition that the mission is to "save the girl and wipe away the debt," the actual mission is to "save himself and wipe away his guilt."

It's not until Booker understands this and that he is also Comstock ("I am both."), coming to accept Elizabeth's judgment as his daughter and victim as well as her powers which he fears more than God ("No, but I'm afraid of you."), that he allows her to give him the true baptism. After the credits roll, he earns a rebirth into another timeline in which he can finally live with himself and provide Anna with the life she deserves.

What are your thoughts on BioShock Infinite? Am I coming out of the left field? Do you agree with some of my points? Did I miss an analytical point you would like to make? Share your thoughts in the comments!