***Spoiler Alert*** (Well, duh… though I'll try to keep things as vague as possible.)

The Stanley Parable, at its core, is an examination of the illusion of choice—and by extension, the illusion of freedom—in game design. Any course about narrative and storytelling in games will have at least one mention of the concept that putting in any story in a game, regardless of how many choices a designer gives the player, is ultimately limited.

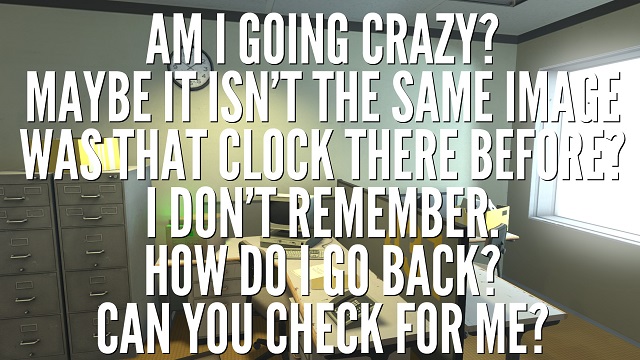

The Stanley Parable itself has multiple endings, about ten or so, and the player has to perform very specific actions, going through very specific doors, to reach each one. It's not so much that the player has the ability to choose freely from a bevy of options as the player needs to pick one of ten linear paths, and a game is only as good as its ability to obscure this fact.

That's why there are so many critically acclaimed games with open worlds and environments. Players can do a whole host of activities in any order they want, but ultimately they usually need to perform a series of specific story missions to "beat the game." Promising free will in a game, a common marketing bullet point, with deterministic endpoints is disingenuous. The only point of difference is Minecraft, which is a set of Legos really, where players have to construct the story himself or herself.

The most ironic ending in The Stanley Parable is the most straightforward one: By following the orders of the Narrator and performing all of the tasks that he orders the player to do like a good soldier, the player will gain freedom! Yay! Sunshine and rainbows! But of course by shutting down the Mind Control Facility, the player opts to be controlled by the godlike voice anyway. The player ends up doing everything that Stanley does at the start, pressing a bunch of buttons that the player is ordered to press.

Any deviance from the main path, and the Narrator, who is really in effect the game designer, either gets testy and puts the player in his place or asks the player about how to make his game better. None of this matters, though. No matter which ending the player chooses, the game just loops on itself and the player is left at the start of the game again. There is no escape from the cycle, no real freedom, no real way to reach the bright, colorful environments hung as pictures on the walls of the office. This emphasizes the game's sense of nihilism, in which all endings are devoid of meaning, though the humor will still likely make the player's experience that much more tolerable… until the player has exhausted all the possibilities. The cycle may be joyless, but the journey doesn't have to be.

At the same time, the Narrator ultimately needs the player, as much as a god needs a follower. In one particular ending, the Narrator struggles to come to terms with an inactive player character who just stands there. There is a dependency between the player and game designer, a symbiotic relationship where player fulfills the raison d'être, the reason for existence, for the game designer… and the other way around. If we're heading into a meaningless cloud of nothingness, we might as well do it while laughing.

Ha ha ha. Ha ha. Ha. ha……