Last Stop is shaping up to be quite an interesting narrative-focused adventure game, one that is a bit different from the developer’s previous title, Virginia. There are still kernels of that dialogue-free title in there, but it mainly pulls from other pieces of media like The Twilight Zone and sci-fi comedy Attack the Block. We recently sat down with Terry Kenny, Jonathan Burroughs, and Lyndon Holland, the game’s three creative co-directors, to talk about the game, its influences, how limitations have shaped the studio, and a bit on how they claim to have not learned anything about game development.

Game Revolution: What did you learn from Virginia? It was pretty unique as in it was a game with no dialogue.

Terry Kenny: It’s hard to tell a story in first-person with no dialogue. I didn’t learn anything because I went to make another video game. Every video game seems to be a weird process. There’s a sliding scale of the joy of it when it is an idea and then the actuality of making it and then you come out the other end… like when we finished Virginia, it was just relief to have finished it. And then we moved on to the next thing and now I am looking forward to the relief of being finished with this game.

I don’t think I learned anything! That sounds terrible, doesn’t it? I am sure I did. I am sure I learned that it was difficult to make a first-person game with no dialogue so that’s why we didn’t do it again.

GR: That’s a really somber answer. [laughs]

TK: It’s been a long day, Michael. [laughs] JB, say something cheerful.

Jonathan Burroughs: During the course of making Virginia, it was very apparent that there are real limitations if you set out to make a first-person game with no dialogue in terms of the kind of story you can tell and the nuance you can get across in the characterization and character performances. I don’t think Virginia is lacking — I think it is coherent within those restraints — but off the back of that, I think we were very keen to do something where there were fewer restraints. Dialogue was an immediate thing that we were really excited about doing. We were timid about it in Virginia, hence imposing that limitation on ourselves and thought we would come back to it another day.

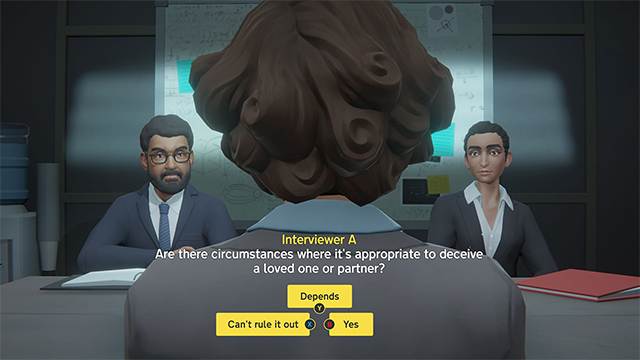

We were excited to do something with multiple protagonists, but the two main things were going from first-person to third-person so we could do something with cameras and interactive cinematography and dialogue and casting actors. It just permits you to do more. Maybe there are an endless amount of Virginia-style games you could make, but it restricted us from telling the stories we wanted to tell. By embracing the things we were excited about with Last Stop, we could tell whatever wanted to. So we decided to tell three stories instead of one.

GR: What do you mean by “timid” with Virginia?

JB: Just in a logistical sense of it being our first game. We had only just set ourselves up as a studio and it was just the three of us. For most of the first year, we knew Terry’s background was animation so we wanted to do something where character animation was at the forefront. And then Lyndon came on and then we knew the music was going to be a big part of that game.

So we thought that was taking on enough of a challenge. The whole process of working with voice actors and casting and just doing that well… I think we had already bitten off enough.

GR: There was around a five-year gap between Virginia and Last Stop. How long did it take for you all to find what Last Stop was going to be?

JB: We were in the wilderness for a while there. Virginia came out in September 2016 and by July 2017, if not before then, we started to have the idea for the game, which was called Moon Lake at the time. The first iteration was quite different; it was set in the United States. But it did have the ambition of being third-person and having dialogue. From the earliest stages, it was going to be an anthology-style thing with multiple parallel stories that take place in the same setting and overlap to some degree.

It felt like a really long time because I think we were worried about going bust. But in reality, it was less than a year to what would become Last Stop.

GR: The writing in this game is pretty good and funny, even for the children and teens. How do you write dialogue for a younger crowd without making it cringeworthy?

Lyndon Holland: I remember having this exact conversation. We had watched Attack the Block and they did a really good job with teens with dialogue and the slang they had. The lengths that they went to get that seemed quite daunting and there were a lot of TV and films that we watched that had teens that [weren’t great]. Because when you get it wrong, you get it really wrong and it’s cringe. So we kind of just wrote them as neutral-sounding adults.

The actors aren’t even teens. They’re in their thirties! So if we had given them whatever the teens are saying today, it wouldn’t have sounded authentic so I am happy we didn’t do that. All I can think about is that Steve Buscemi meme.

GR: There are some supernatural elements like Virginia. How do you make a story like that grounded when interdimensional doorways are opening up?

TK: Those kinds of stories are always appealing to me. It’s just a media diet someone grows up on like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits. Those are the kinds of things we throw around at the very beginning.

But keeping it grounded was intentional. We wanted it to be relatable stories to happen against the backdrop of something supernatural. Like Donna’s story is about finding her relationship changing between her group of friends and family. Paper Dolls is about a single father struggling. Domestic Affairs is someone struggling with their work life with their home life. A lot of time went ensuring that no matter how fanciful stuff gets, we wanted the characters to feel relatable and they are normal people who are having crazy things happening to them.

GR: Jump cuts were Virginia’s thing. And now it seems like you guys are playing with a cinematic camera. Can you elaborate on that decision?

LH: From a pragmatic viewpoint, we didn’t want to rely on waypoint markers so the camera leads and, in certain scenarios, moves with the character to suggest where you should go. But also we tried to give the camera some character. None of us are cinematographers in the traditional sense, but there’s a lot you can suggest about a tone by the way the camera is positioned. So having characters far away from the camera suggests distance between those characters. Close up shots suggest intimacy. Camera angles from within cars suggests someone is watching.

We wanted to use tricks like that. And also the flair of it all. Like if there is a piece of music swelling, the camera can sort of going into a crane shot and give an establishing shot of where the character is going and expand the character’s feeling into something bigger.

GR: There are a few little mini-games in Last Stop where you mimic a character’s actions and it’s a pretty apt way to inject interactivity. Games in this genre usually struggle with that so how did you go about it so it wasn’t just a string of quick-time events?

JB: Those interactions should always be driven by the characters as well as being able to break up the routine enough and reveal something about the character for a moment. John’s interaction lets players role-play and it reveals the monotony of his work. That ambition was that they’d have some sort of dramatic ambition to them.

The one with the pictures on the phone evolves over the course over the game. That has an emotional dimension as well and reveals something about the characters and the family and friend relationships that we don’t see.

GR: The game has featureless mannequins as NPCs. Is that an artistic decision or is it because the game is not done?

TK: A combination of style and limitations. We did try a couple of things. We felt happy, and this sounds cynical, but we thought it was fine for a big city. We don’t have the ability to have self-generating versions of lots of different characters. It would draw attention to them. Like you can have a handful of background characters but none of them are distinct. ‘It’s the dude in the pink shirt again!’ [laughs]

So they’re all muted colors with blank faces. You know you won’t be getting quests off people on colors so they blend in and hopefully your eyes are drawn to the other characters. I’d love to say that this was all some fantastic idea.