All the spoiler alerts go here.

My absolute favorite aspect of Ether One is the organically integrated puzzles. I didn’t expound on them at length in my review because they were really a series of tasks—you have to recreate daily life in and around Pinwheel, but figuring out how to do so is a puzzle itself, one whose solution I didn’t want to reveal. But now, time has passed, and you’ve hopefully played the game, and I’d like to look further into what normalcy truly means for this title.

The world that you, the anonymous Restorer, are dropped into is supposed to be a real place as remembered by a dementia patient, Thomas Fletcher. (Initially, the game would have you think the mind belongs to Jean Thornton, his wife, via some misleading clues.) Thomas was a miner like his father in the Brimclif Mines who sadly underwent a lot of trauma: His father was an abusive drunk, his mother left them to save herself, and Thomas barely escaped the mines after they flooded on May Day in 1966.

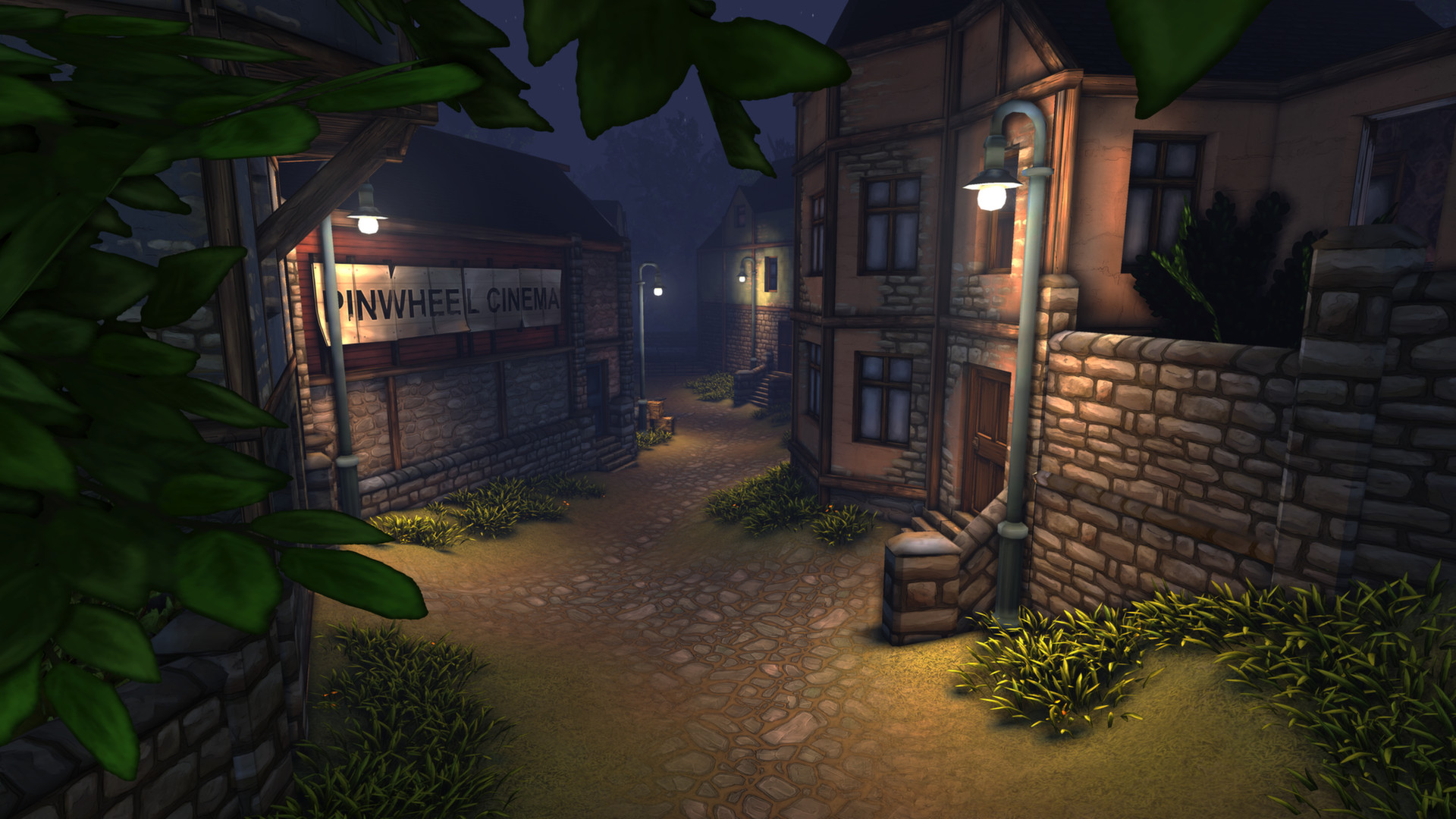

Pinwheel, as you explore it, is not so much a real place as a symptom of the trauma Thomas has experienced. After all, a town bereft of its citizens is not particularly welcoming. No matter the amount of holiday decorations and charming homes and buildings, the emptiness becomes palpable. You, as Thomas, are alone in this world, and the only means of escape is restoring fragments of your memory and validating your life experiences.

The easy path through the game has you grabbing red bows, which possibly belong to Jean, slowly constructing a ladder out of dementia’s grip, but the ending earned brings mostly lucidity back to Tom. It’s not the cure that your employer, Phyllis Edmonds, is seeking. No, in order to really recover, the memories of a lively Pinwheel need to be re-established, and that is only done by fixing projectors in each area.

When you fix a projector, the nearby area is suddenly full of noise. The school in Pinwheel Village echoes the children’s laughter in its yard. The Crow’s Nest bar booms with joyous singing of a shanty written by a village local. And the showers in the Miner’s Dry at the Industrial Centre are filled with men chatting after a long day. This is normal. A resident or worker here would remember vividly how all these sounds meant day-to-day life was pacing along.

But if you examine the tasks that restore what is normal, something doesn’t add up. For example, in the Miner’s Dry, you have to carry out a revenge plot on the Warden by a disgruntled miner, Sean Vannerman. The tasks are simple—put arsenic in the coffee machine, find the Warden’s favorite mug, fill it up, and place it on his desk. Although suspiciously morose compared to other things you find to do in Ether One, this “puzzle” doesn’t have you shifting strange blocks, learning an alien language, or enchanting items. There’s nothing immediately strange or unfamiliar about it.

The issue here is that Thomas Fletcher would know nothing of these tasks. It wasn't his plot to kill the Warden, and Sean’s threats would not have been widely known to coworkers unless they opened his locker. The murder plot is emergent as well in that you find the items and do the math in your head based on notes on how to clean the coffee machine and the secretary’s morning checklist, the latter of which Tom probably never noticed.

The question remains: How much, if any, of Pinwheel is real? The tasks you complete, such as activating Alexander Graham Bell’s machine, completing a shipment of hard cider, and tuning a grinding wheel have nothing to do with Tom, so there’s no reason you should have the pieces or know-how to finish them.

In fact, if this was really someone’s dementia-addled memory, you would find more gaming tropes in place. Most building interiors would be inaccessible with locked doors, only viewable through windows. Items wouldn’t be moved around as freely, and there certainly wouldn't be so many of them. Entire areas would probably be seen at a distance with no real way to reach them. Hell, this world could be reduced to a ton of invisible walls or barriers, such as those that were commonplace in the Assassin’s Creed series.

Yet it’s not. And it’s not just the tasks that muddle the image. There are lots of letters and notes between residents of the town. One note is from a mom talking to Sean’s wife, Jacqui, about what a handful her boys are. There’s a journal from one of the Post Office workers, complaining about the heavy items Bell orders all the time. In the mines, there are letters from residents to their dead family members who perished in the flood. The basis of fixing the projector at the church is reading someone’s note on how he loves the piano but hates the bells that play with it.

While all these things contribute to feeling at home in Pinwheel, both by establishing a lived-in world and by assisting with helping out the citizens and local businesses, they are impugned by close examination. Perhaps that is part of the message of the narrative.

When you stroll into Pinwheel, it’s empty and eerie, but it becomes a second home as you run around fixing and doing things, getting to know the locals. What eludes you is that this is a world you need to escape, just like a dementia patient needs to let go of his perception of reality and of memories holding him back but can’t. There isn't safety in being here, as the few cut-scenes are wont to remind you. Pinwheel is a false haven whose siren song is played on an inaudible frequency and you are shipwrecked on its shores. (Try wading out into the water by the harbor.)

It’s impossible to tell how much of this concept was intentional on the part of the writers. Tom’s story is told through far more apparent means, and at first glance, the world in his mind only contributes to that. Below the surface, though, is an urgent narrative, one where the player is drowning alongside the patient in a sea of confusion but doesn't realize it.