[Is it possible that the rise of the Evil Casual Gaming Empire isn’t such a bad thing after all? Casual Difficulty considers the effects—both good and bad—that casual gaming has had on hardcore gamers. Think of this semi-regular column as a peace pipe extended from our gnarled FPS-worn hands to the soft, innocent hands of our casual brethren and sistren. In this Casual Difficulty, a look at games’ shrinking lifespans.]

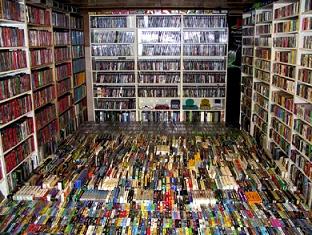

Most of us have an elaborate system for selling, trading, storing, or collecting the games we’re done playing. Entire segments of the gaming industry are devoted to finding new homes for the titles we no longer want. Like a bunch of bad pennies, the games that were huge sellers twenty years ago keep turning up in stores and online—endlessly cycling and recycling.

So it probably goes without saying, games rarely end up in the trash.

But this generation of consoles has seen the advent of a new way of thinking about the lifespan of a game. And it’s impossible to see yet what effect this will have on how we value the games we play. I’m referring here to cheap, abundant downloadable titles.

These are games we can’t get rid of or throw away. We can’t sell the licenses to these games. We can’t trade them in. There are no physical discs to sell or give to someone else. Once we buy them, we are stuck with them. Worse, we don’t know yet if we’ll be able to transfer these games to the next generation of consoles. Will the free games on Playstation Plus for PS3 be available on the PS4?

Thus far in prior columns, I’ve been pointing to the ways that the casual gaming market has been good for us more traditional (“hardcore”) gamers. But this is my first turn toward an aspect of casual gaming that could actually be bad for us.

Runaway downloadable hits like Uno, Fruit Ninja, and Peggle have been fantastic boons to gamers and publishers alike. But they—along with games with more hardcore appeal like Trials HD and Braid—have also solidified a new type of ownership. Paradoxically, by making these games impossible to get rid of, publishers have also made these games utterly disposable.

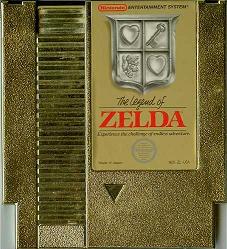

Let me explain what I mean. When we purchase a downloadable title, there’s a built-in expiration date. Sure, discs and cartridges are also susceptible to the passage of time, but there’s a sense—especially among collectors—that if we take appropriate care of our discs and consoles, they’ll last a lifetime. Moreover, by selling or trading or simply giving a disc or cartridge to someone else, we ensure that it continues to be played and appreciated. And when those folks are done with it, they pass it on yet again. A game can eternally stave off the landfill as long as it keeps passing from person to person.

But like summer love, we know that a downloadable game might only last for a short season (say, the lifespan of a console, or at best, the lifespan of a publisher). The items we’ve purchased in Farmville won’t last forever. Social games, like many multiplayer FPSs, will only last as long as there are servers to support them. Because we can’t pass these games along, their lives will end when their supporting infrastructure dies.

But like summer love, we know that a downloadable game might only last for a short season (say, the lifespan of a console, or at best, the lifespan of a publisher). The items we’ve purchased in Farmville won’t last forever. Social games, like many multiplayer FPSs, will only last as long as there are servers to support them. Because we can’t pass these games along, their lives will end when their supporting infrastructure dies.

This isn’t to say that these games and downloads aren’t worth the money. Oftentimes, they’re much cheaper than full retail discs; hell, some are even free. If we calculate the amount of enjoyment we get from these games relative to the amount of money we pay, we generally end up well ahead.

However, “value” is a tricky thing. I’m not really talking about money, but rather about something less tangible. I’m talking about the value we put on certain games in our collection that we’ve held onto for years, possibly decades. Those games that are dear to us for reasons we can’t really explain. Games that we’re willing to spend outrageous amounts of money on just to have a physical object to hold onto, caress, and occasionally talk dirty to.

Maybe we’ve held onto our gold copies of NES Zelda cartridges. Maybe we’ve still got our physical copies of Rez, Ikaruga, or Marvel vs. Capcom 2 for the Dreamcast stashed away in a drawer (or framed in a plastic case surrounded by laser-sight security cameras). But even if we don’t, there are certain games to which we attach a strong personal value that for some inexplicable reason is more valuable when we’ve got a thing to look at and put away somewhere safe.

Back when new technologies were invented for copying famous paintings (so that we could all hang perfect copies of the Mona Lisa in our living rooms), there was a real fear that people would no longer think of art the same way. We feared that we’d lose touch with the magical “aura” of the thing itself. And we largely have. But whether that’s good or not still remains a question.

Undoubtedly disc-based games will continue to be made for a long time to come. But even those now come with so many downloadable add-ons, extras, and multiplayer-only modes that the difference between disc and download is entirely moot.

Undoubtedly disc-based games will continue to be made for a long time to come. But even those now come with so many downloadable add-ons, extras, and multiplayer-only modes that the difference between disc and download is entirely moot.

Our games are less “ours” now than they’ve ever been, and their lives are much more fragile. It isn’t money we’re losing, but some deeper, more personal investment in the games we love.

We all know the myth of the landfill in New Mexico filled full of copies of unsold E.T. cartridges for the Atari 2600. If there’s a lesson to be learned from that myth, it’s that the greatest sign of our ability to truly value something might be the ability to toss it in the trash.