Reviewing games professionally might seem easy, what with user ratings and user reviews everywhere (Steam, Amazon, GameFAQS, etc.). But cranking out a comprehensive argument with a deadline before the game's release date is harder than it looks. Readers expect—or should expect —reviewers to give a fair shake of a game and have enough experience with the franchise and genre to highlight a game's strengths and weaknesses properly. That's supposed to be the easy part.

But there are many more constraints to professional reviewing, apart from being unceremoniously thankless at times, that you might not realize which can make a reviewing a game different from merely playing a game. Here is just five of those differences.

1. Time Crunch

First and foremost, reviewers have a deadline. Whether it's pushed by the outlet itself or a specified embargo date—a time given by the publisher that determines when reviews can be posted— reviewers need to speed through a game. Usually, this embargo time is the release date or the day before that, so the intensity of this time crunch will depend on when the reviewers receive the retail game or a reviewable build of some form (sometimes a direct code and sometimes a build on a debug console).

Even so, reviewers are asked to get through the game quickly enough to hit the standard deadline from their editors which can be as expedient as “as soon as possible” or something less stressful like “within seven days”. The deadline is even tighter if the reviewer is locked behind closed doors at a review event and only has a day or two to experience the game. (Hey, play Metal Gear Solid V in two days. Good luck!) Usually more time is given for lengthy RPGs, though most publishers with a game that takes longer than 30 hours to complete will (hopefully) give enough advanced lead time. Ultimately it's up to the reviewer to determine whether he or she has had enough time with the game to review it properly; typically, that's finishing the game and exploring all of the game's modes, though the parameters can be less exact than that.

Whatever the time crunch, reviewers are expected to zip through the main content of the game which can mean playing it from anywhere between two-hour spurts each day or 10+-hour marathons (more likely, the latter). This is where reviewing a game is most different than merely playing a game, as some games are just better played in short sessions rather than lengthy periods of time, when repetition can be more easily experienced (especially if the gameplay is unbearable). Almost any game can become boring after doing the same set of actions over and over again, but unlike playing a game normally where a player can just drop the controller, reviewers need to grit their teeth and continue to move forward.

Luckily, reviews-in-progress are much more common nowadays to respect both the time crunch and the reviewing process itself. These are particularly necessary for games that require a large online presence to review correctly and have online servers (SimCity, anyone?) that need to be tested before a final assessment can be made regardless of the timeliness that an early review would provide.

2. We Can Only Review What We're Given

By this, I mostly mean the physical. Reviewers typically receive the base game, which can be a different experience from receiving a Collector's Edition with multiple pieces of swag or even just a game with pre-order bonuses. Most of the time, we are given only the bare minimum, not out of spite or anything like that (in my experience of course) but because the products or materials just aren't ready by the time outlets need a game. This can be especially frustrating if pre-order bonuses are tied to special story missions or special unlockables that make the game easier or better.

This becomes more of a problem for the toys-to-life genre where the game can change dramatically depending on which figurines are sent to outlets and which aren't. There can be entire sections of the game that can't be accessed, let alone the experience of having the full set in the first place, without having a particular figure. But we can only review where we're given, so if these sections would have made the game feel more complete, that's just too bad.

That said, the games we receive are technically free, though occasionally reviewers do need to spend money out of pocket. Reviewers need the discipline to look at these review packages not as gifts but as assignments, which isn't difficult when professional reviewing becomes your livelihood. As a coincidental side effect, it does relinquish reviewers from post-purchase rationalization, a cognitive bias that has consumers overlook flaws for products, notably expensive ones, they purchase.

3. We Can Only Review What's Available

For better or worse, games are no longer fixed products when they're released. Some games have extensive day-one patches and others have an outlined plan of content that adds or completes a game over time, whether it's raising the level cap in an MMO, unlocking new multiplayer modes, or even having time-locked features as in the recent Super Mario Maker. But reviewers can't review something that doesn't exist. As such, review updates have been becoming increasingly more common, though it does speak to the unfortunately static nature of review aggregator sites (but that's for an entirely different article).

Multiplayer modes sometimes just aren't available at all because the servers aren't live before the game's release date, but publishers understand this problem which is why reviewers attend either multiplayer events or have access to a special early-access server. Of course, this means that we're stuck with playing against other critics, journalists, and developers, which is different that the typical pool of players.

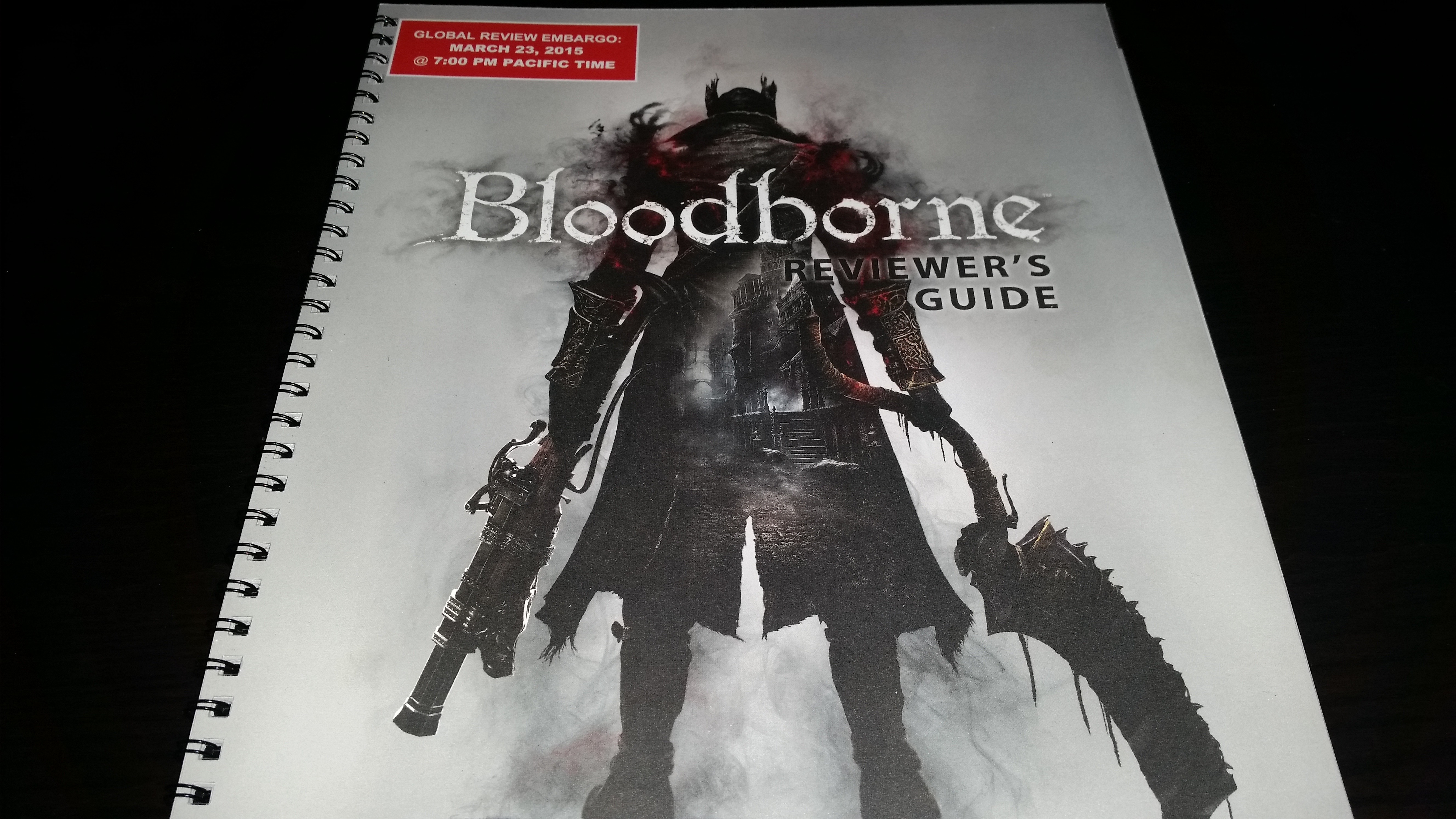

4. Review Guides

Review packages tend to arrive with a fact sheet that provides a quick rundown of the game as well as a review guide of sorts. This isn't meant to tell reviewers how to review the game, but more about letting us know about all the features that the game has, features that we might miss (especially given the time crunch). This can be anything from new unlockable modes, items, or particular strategies that we might not consider.

Of course, any reviewer understands that these review guides are mostly positive in nature, and it's up to us to pinpoint any faults with the game that the review guide doesn't cover. That said, the review guide does give us a slight leg up when it's available, though for the most part, it servers as a helpful reminder of what's available in the game at that point in time.

5. Reviewers Look for Strengths and Weaknesses From the Very Start

The point of a video game, as many would say in a straightforward fashion, is to have fun. Just sit back, relax, and enjoy the game for what it is. Reviewers don't have that luxury, though reviewers do need to want the game to be good before they begin. Unless the game is absolutely amazing throughout the entire experience, we're supposed to be critical about a game and not let things slide even if ignoring it would make our experience more pleasurable. Ignorance may be bliss, but if you ignore every problem, every game would be perfect, right?

Reviewers, even if they greatly appreciated a particular franchise, genre, or developer, need to have a heightened awareness to point out the flaws of the graphics, sound, gameplay, and story. Yet at the same time, it also takes a certain sense of discipline to let the game's strengths shine through and to allow yourself as the player to be amazed. Putting on the reviewer hat too snugly can make everything feel imperfect or mediocre, and reviewers need to be open to both sides of the critic's coin. This doesn't mean being middle of the road and not having enough courage to speak truthfully; otherwise, what's the point?