Keeping it in the family.

Comedian Louis CK does this great bit about parenting where he discusses how easy it is to inflict psychological damage on your kids via a few simple mistakes. As with all of CK’s work, it’s brilliant in its brutal, unflinching honesty, and though I’m not anyone’s father, it made me appreciate how difficult it must be for moms and dads to successfully raise a child. From its premise, I thought developer Kent Hudson’s The Novelist was going to give me an accurate glimpse into how the tough decisions a parent unwittingly makes has a detrimental impact upon their offspring, but this is unfortunately not the case. What The Novelist instead offers is a meandering and, due to a flawed conclusion, insincere take on suburban family life.

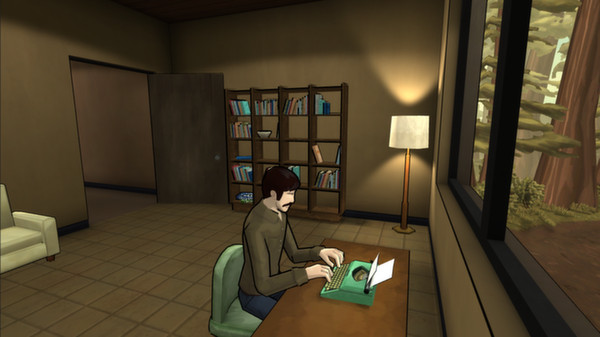

The Novelist puts the player in control of a voyeuristic spectre, floating around a holiday home rented out by the troubled Kaplan family. The Kaplans are Dan, the struggling writer husband who is drinking too much and spending too little time with his loved ones; Linda, the artist wife who is contemplating the future of her marriage; and Tommy, their troubled child with suspected learning difficulties, who was taken out of his previous school due to him being bullied.

Your job is to float around the house and explore their memories in search of clues, which will then indicate the desire of each character for that particular day. You will then have to make a decision regarding which character’s desire you wish to fulfill, which will have negative consequences for those you have ignored. In the majority of the chapters you can also choose to select one compromise, meaning that a character won’t have their wish granted, but will at least experience some semblance of happiness. You decide which character you wish to appease by finding the item relevant to their need (for instance, if Linda wants to go camping, you go find her backpack) and then eerily whispering it into Dan’s ear while he is sleeping.

There are two ways to experience The Novelist, either in Stealth or Story mode. Stealth is the default option and will see you trying to navigate the house without being detected by the Kaplans by ‘possessing’ light bulbs. Sometimes the Kaplans will switch off certain lights, which will make your job a little more difficult, but it rarely becomes challenging. If they spot you, they become a little shook up, but you’re given enough time to disappear quickly back out of sight again. However, if they see you out in the open for too long you’ll be rumbled and will be placed back in the living room again, though the progress you made in the chapter will be saved. This makes being detected little more than a minor inconvenience, and the few times I was spotted were largely due to my own impatience in waiting to pick up a clue that they had all irritatingly gathered around. Story mode is perhaps the preferable option, as this makes you undetectable by the Kaplans and therefore free to pick up clues as you wish.

But while you are placed in control of a ghostly presence in the Kaplan’s home, you’re ultimately a passenger barking (or, in this case, whispering) orders at Dan from the backseat, as he is posited as the glue that holds his small family together. While this initially leads to much anxiety for him as he struggles with balancing the completion of his latest novel with being a good family man, these issues can be rectified with a few, simple compromises. Though the decisions you’re asked to make differ in each chapter, they ultimately boil down to Dan spending time with Linda, Dan spending time with Tommy, or Dan doing something in order to further his writing career. You’ll run into no small amount of moral difficulty when you find yourself neglecting Tommy in order to ensure the stability of your relationship and career, and during my initial playthrough I found myself often ignoring his requests to build a fort, help him with his homework, or have Dan become something other than an emotionally vacant father in favor of repairing his relationship with Linda and continuing his literary pursuits.

However, despite Dan’s frequent selfish decisions and his ignoring of Tommy, the end of each chapter frequently ends in a weirdly upbeat fashion. I wasn’t anticipating The Novelist to be overly optimistic, and while this isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, by the time it reached its conclusion its positivity felt dishonest. There were so many missteps I had allowed Dan to make as both a father and a husband, yet he barely suffered any repercussions. Gone Home, another game that resides within The Novelist’s “thoughtful point-‘n’-click” genre, was also an optimistic tale, but one that was told with incredible sincerity and therefore packed a hard emotional punch come its concluding moments. The Novelist doesn’t have that.

I’m still happy that these kind of games are being made, and particularly that they’re being supported by the gaming community itself via Steam’s tremendous Greenlight system, but while The Novelist certainly has a particular charm with its minimalist visual style and unique concept, I felt underwhelmed by my experience with it. Ultimately, The Novelist was not the Pulitzer Prize winner that I was hoping for, but rather a fairy tale for grown-ups who want to believe that, no matter the outcome of their decisions, somehow things will work out for the best anyway.

-

An endearing minimalist visual style

-

An all too optimistic take on the hardships of family life

-

Stealth mode adds nothing to the game other than mild irritation

-

A unique, mature concept…

-

…with a narrative that isn’t half as interesting as its premise