Sea of Solitude is an openly allegorical game based on creative director Cornelia Geppert’s struggles with mental health and trauma. Rather than an untarnished hero, Kay is flawed and imperfect. She is openly aligned with the developer who has drawn on a story of heartbreak to make the game. In this game, the monsters aren’t respawning, run-of-the-mill slash and hackers. They’re manifestations of Kay’s trauma which she must overcome to succeed, which probably hits a little close to home for most people. While not exactly subtle, this game shows the internal problems many of us suffer from. And that approach is a novel things for video games.

But why? 300 million people worldwide suffer from depression, and the taboo of silence around this is slowly being lifted even in some video games. Existential fear is almost passé at this juncture. Our world’s on fire, the oceans are filled with plastic, demagogues are taking over countries, and it’s all getting quite spooky. No one is denying that Resident Evil 7 didn’t ruin our lives and sleep patterns possibly forever. However, external terror can only take us so far. It’s clear that the true horrorscape is the inside of our own mind. Sea of Solitude takes this on by forcing Kay into close quarters with her own flawed self. Forget ghosts and ghouls; true horror is facing up to ourselves, with no distraction, and nowhere to run.

ALSO: Sea of Solitude Review | Lost at sea

Turning from traditional enemies

The good versus evil binary has been at work for thousands of years. It’s an essential staple of video game narrative. Trials, allies, and villains are essential in the traditional hero’s journey, and this usually forms the structure of most video games. Think Bowser for Mario or Dracula in Castlevania. It’s the simplest construction to create drama. Pit a character against their respective villains and force the player to bring the hero to victory. It’s fairly common for the villain to fall on their own sword, or become victim to their own hubris; the quality which the hero has to fight hard against in themselves.

And so, the villain holds the flaws of the hero, which is a physical manifestation of the worst of themselves for the hero to fight against. It’s part of the reason a player feels triumph and delight when they win against the bad guy. Sure, Bowser is awful for taking Peach hostage. But isn’t there a little bit of Mario that desires almost the same thing? By defeating Bowser and freeing the princess, Mario can win all that Bowser had and the moral high ground to boot.

The wins are not so cut-and-dried when the villain is internal, however. A certain level of self-evisceration is needed to triumph over inner adversity. The level of self-evisceration required in order to triumph over internal difficulties is eye-watering. This is what Kay goes through in Sea of Solitude and the raw, emotional openness is a gut punch to a player. Mental health has been a taboo topic for a long time. With the changing tide of information and cultural openness, the unspoken is being stripped away. It makes sense that games would eventually move into this space.

Why is introspection so frightening?

And move into that space they shall. The Towerful of Mice ghost from The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt might reguarly invade my nightmares, but there can be few things more terrifying than the contents of your own mind. Games are starting to include the mechanics of internal horror as the show-stopping villain or creature in recent releases.

In Sea of Solitude, Kay has to navigate the waterlogged city but must deal with the creatures that she encounters, representing familial traumas and the elements of self-doubt and loathing which all featured in the rough break up of the developer herself. It’s common to fear to be alone with your thoughts, and Kay’s journey is a real example of this.

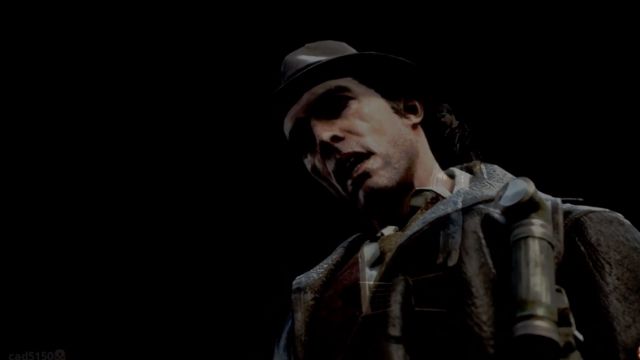

Things get a little trickier in something like The Sinking City, however. Here, Charles fights hysteria and insanity in the Lovecraftian hellscape in which he finds himself. It’s interesting to find a male figure in this sphere, particularly considering that era chosen for The Sinking City, when male mental health and insanity, in general, was seen as the unfortunate reserve of the female.

Video games have offered escapism and fantasy of almost unfathomable heights since its creation. It’s not surprising that the thrust of introspection into this sacred sphere of escapism makes us clammy. Gaming is the area of our lives where reality cannot invade. It’s uncanny to see our avatars struggling with inner demons, just like us. Games need to continue to push and discomfit their audiences as reaching deep into the bank of shared trauma is a good way to keep us on our toes and expand the medium in a way that fits with today’s increasingly more progressive views on mental health. Talking about it is good and video games want to be a part of that conversation.

Tears for future fears

Sea of Solitude is not the first of its kind, but it is unusual in branding itself as a foray into internal conflict from the first text scroll. We’re seen a little already in Silent Hill, and recently The Sinking City gave a nod to the destabilizing influence of mental health. Senua’s Sacrifice cannot be left out of the conversation either, given its heart-wrenching portrayal of psychosis. Something has to make the bold move to usher in the rest, and that might be Sea of Solitude‘s role, even if it isn’t doing that pushing by itself. It has certainly opened an enormous forum online of people sharing their personal difficulties, and what they took away from the game.

Gaming has always held an element of solitary confinement. Certainly, multiplayer is sociable, but the usual experience is self-immersion. Since you’re already playing solo, it makes sense for games to push your notions of internal stability. Sea of Solitude might have numerous weaknesses but it’s yet another game willing to try to destigmatize mental health issues; a goal that fits with the recent push to speak about those previously unspoken topics. In another guise, this unflinching call to self-analysis has the potential to really make waves and inspire other games to be bold and talk about the subjects we don’t always want to talk about.