[Is it possible that the rise of the Evil Casual Gaming Empire isn’t such a bad thing after all? Casual Difficulty considers the effects—both good and bad—that casual gaming has had on hardcore gamers. Think of this semi-regular column as a peace pipe extended from our gnarled FPS-worn hands to the soft, innocent hands of our casual brethren and sistren. In this Casual Difficulty, a look at stories in games.]

In contrast to other narrative media—like novels, films, and comics—the majority of game stories seem like the grotesque product of a million adolescents furiously typing on a million greasy keyboards for a million awkward years.

There are a few notable exceptions, of course, but by and large game narrative hasn’t evolved as much in complexity compared to the medium’s other advances. Graphical effects, control mechanics, online functionality, and so on, have all progressed by leaps and bounds over the past three decades. But we’re all still killing ugly space aliens just like we were thirty years ago in Tempest, Galaga, and Space Invaders.

It’s distinctly possible that games just aren’t very good at telling stories.

We don’t play board games for the storylines, nor do we read poetry looking for profound plots. Both of these things can tell good stories—tabletop RPGs and epic poetry both tell great stories—but that doesn’t mean that they all should.

As I claimed in a prior column, one of the great boons of casual and social game design is that mass-market-friendly titles are turning back the clock to a time before games were unnecessarily complex. Part of this reinvention has been the ousting of typical game narratives.

Like every other gamer, I’ve become accustomed to the derivativeness of game storylines. Over the years, I’ve even grown to appreciate the subtle differences between them. From the perspective of a gamer, the alien invasion story of Half-Life 2 is worlds apart from the invasion story of Gears of War. But to a non-gamer, they may as well be the same game.

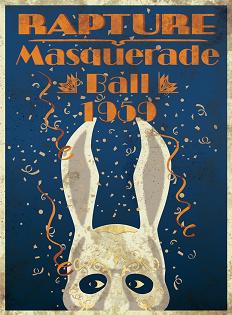

Just like controller complexity has alienated a large part of the population, so have the outlandish science-fiction storylines. But rather than ditching narrative altogether, casual genres like mini-game collections and social games rely instead on a sense of setting – a farm, outer space, a carnival, a kitchen, a tropical resort, a yoga studio, a suburban neighborhood, etc. – but not necessarily on plot.

Just in case you were sleeping, absent, or just plain spacing-out during your high school English classes, “plot” refers to the interrelated events within a narrative and “setting” to where and when those events take place. Both are aspects of storytelling, but as casual gaming is showing, games as a medium might be better suited to setting than to plot.

Just in case you were sleeping, absent, or just plain spacing-out during your high school English classes, “plot” refers to the interrelated events within a narrative and “setting” to where and when those events take place. Both are aspects of storytelling, but as casual gaming is showing, games as a medium might be better suited to setting than to plot.

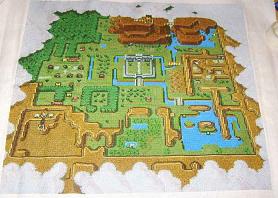

I won’t go into too much detail about why this is the case, but I will say briefly that—unlike every other storytelling medium such as novels or movies—games are defined by non-linearity. Even the most rigidly linear game needs a certain amount of wiggle room to allow players to make choices. Sometimes it’s as simple as choosing when to push a button (like in Dragon’s Lair); other times, it’s as complex as wandering about an entire continent and doing whatever strikes your fancy (like in Daggerfall). Similar to sports, video games depend on having a clearly defined space for things to happen, but not a scripted course of action.

The open-world and sandbox genres take setting very seriously. The skeletal story that weaves together Just Cause 2, for example, is nothing compared to the island itself. Or think about how vital the setting is to a recent critical darling like Batman: Arkham Asylum. Yes, these games also have plots, but comic books and TV shows could relay those same plots far better.

What games uniquely offer, however, is an experience that depends instead on developing a feeling for where you are. A quick glance at the highest-rated games of the past few years indicates just how important setting is: Grand Theft Auto IV, Bioshock, Super Mario Galaxy, Uncharted 2, Mass Effect 2, Red Dead Redemption, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. It’s far easier for us to remember where these games take place than it is for us to recall what happened in them. This is what immersion is really about.

Part of what makes crowd pleasers like Rock Band and Mario Kart so successful with non-traditional gamers is the almost total absence of plot. This isn’t because non-gamers “don’t get it”. It’s because plot oftentimes gets in the way of a great game experience.

Part of what makes crowd pleasers like Rock Band and Mario Kart so successful with non-traditional gamers is the almost total absence of plot. This isn’t because non-gamers “don’t get it”. It’s because plot oftentimes gets in the way of a great game experience.

You can sympathize with the thoughts of a non-gamer: “I don’t want to know the history of the Zerg or the reasons for Captain Price’s imprisonment. I just want to play the damn game.” There’s an endearing honesty to that attitude.

Last year’s surprise hit Demon’s Souls was striking for many reasons, but From Software’s most daring innovation was making a long, complex RPG with almost no plot. Instead, the game oozes with atmosphere and a strong sense of place. And what keeps the game from feeling like an endless and monotonous grind are its memorable locales.

The plot of Demon’s Souls is no more intricate than is the plot of Super Mario Bros.; yet its settings are as complex as any virtual world could hope to be. Likewise, MMO designers have recognized that not only is plot difficult to do on a massive scale, it’s just not necessary. Most MMOs rely instead on conveying a unique history, culture, and geography—that is to say, setting.

Until recently, I had thought that it was my fault that I couldn’t stomach bad game writing, clunky dialogue, and amateurish voice-acting. But as the explosion in casual game design has shown me, the fault may not lie with me. Nor do I blame bad or untalented writers. The real problem may be that we’re trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

Perhaps we could all use a good mini-game enema now and again.