Is it possible that the rise of the Evil Casual Gaming Empire isn’t such a bad thing after all? Casual Difficulty considers the effects—both good and bad—that casual gaming has had on hardcore gamers. Think of this semi-regular column as a peace pipe extended from our gnarled FPS-worn hands to the soft, innocent hands of our casual brethren and sistren. In this Casual Difficulty, a look at genre categories.]

Gamers are no strangers to obsessive compulsion. We love to collect. We love to look for patterns. We love to strategize. We schematize AI and human behavior alike. Like Neo, we see in games the numbers behind everything.

So it comes as little surprise that we also love to categorize the games we play. Just like friends and family want to know the sex of a newborn child, gamers desperately need to know a game’s genre.

Even if “puzzle-platformer with survival-horror elements” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, we’re so fluent in the nuances and conventions of genre that we can all say things like that without much thought. Even more incredibly, we all know exactly what it means. Hell, you all probably had some images pop into your head just reading that description.

After the release of Alan Wake, there were dozens of ongoing discussions about what to call it. Is it a survival horror game, or an action thriller? Or is it some long-winded hybrid like “survival action thriller with cinematic horror aspirations”? Regardless, if you've played it (and you all should), you probably also have a strong opinion as to its genre.

I wonder, though, what this does for us as gamers. How does this affect our enjoyment of a game? Are we simply victims of effective niche marketing, or are we instead expressing our natural inclination as gamers toward compulsive systematization? I don’t have any hard and fast answers to these questions, but I do want to consider some alternatives to our genre obsession.

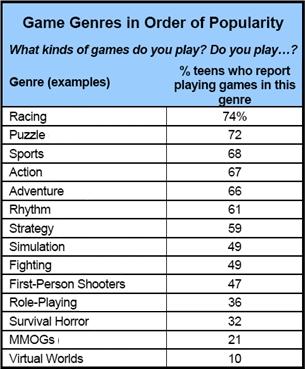

Once we start looking at what we broadly refer to as “casual games”, we begin to see very little in the way of genre categories or familiar genre conventions. What is Fruit Ninja? What about Cooking Mama? They both use gesture-based mechanics and are lumped together as “casual games”, but what do we call them? I suppose we could call Fruit Ninja part of the “finger-slice” genre, and we could call Cooking Mama a “gesture-based mini-game collection in the style of a how-to game”. But why would we, especially if we—as traditional or “core” gamers—aren’t the ones playing these games?

Because casual gamers aren’t as versed in gaming history and gaming conventions, they don’t have the same vocabulary as we do for describing the games they play. And even if they did, they’re not nearly as invested as we are, so they probably wouldn’t care one way or the other whether Metal Slug is a “non-aerial side-scrolling shooter” or a “2D run-and-gun platformer.”

Because casual gamers aren’t as versed in gaming history and gaming conventions, they don’t have the same vocabulary as we do for describing the games they play. And even if they did, they’re not nearly as invested as we are, so they probably wouldn’t care one way or the other whether Metal Slug is a “non-aerial side-scrolling shooter” or a “2D run-and-gun platformer.”

The benefits of not caring are all on the design and development side of the equation. If designers don’t feel beholden to their audience’s need to categorize, they also don’t feel beholden to the same familiar ideas and conventions. At least part of the reason that we gamers love sequels and samey FPSs is because we’re victims of our own genre obsession. Like people who truly have OCD, we may have become debilitated by our own compulsions.

As much as we want to blame publishers when we see derivative games like Dante’s Inferno, we need to understand that publishers are also catering to our own desire for familiar tropes. They know that if we can’t categorize it, we won’t play it. Games that try to shatter conventions—Ico, Rez, Mirror’s Edge—have a habit of being relegated to “cult classic” status and only enter the mainstream after years spent wallowing in relative obscurity or, in the case of Mirror’s Edge, utter calumny.

It’s more than a little interesting that the games that have recently been credited by gamers and the gaming press with being so unconventional and groundbreaking don’t break genre conventions. Instead, games like Braid and Limbo deliberately look backward to well-established conventions of 2D platforming, and a game like Bioshock holds firmly to FPS tropes (even if it does ultimately turn them on their head).

I could simply say that we need to “get over it” and just let games be games, but I know and you know that that won’t happen. On the contrary, some of the biggest revolutions in traditional game design have come from diving whole hog into—rather than away from—familiar genres. Modern Warfare didn’t establish a new genre; it refined it.

I could simply say that we need to “get over it” and just let games be games, but I know and you know that that won’t happen. On the contrary, some of the biggest revolutions in traditional game design have come from diving whole hog into—rather than away from—familiar genres. Modern Warfare didn’t establish a new genre; it refined it.

But at the same time, an even bigger and more widespread revolution is happening in the casual market where games have far fewer categories, where the people who play them don’t call themselves “gamers”, and where they may not even know the name of the game they’re playing—let alone its genre. Even if these players don’t seem as engaged in the culture of gaming as we are, they’re every bit as excited by the games themselves.

This isn’t an “either-or” proposition. I’m not telling anyone that they need to stop categorizing games. That would be like telling us not to obsess about Achievements or kill-death ratios. But I do wonder what might happen if designers didn’t feel the need to cater so much to our obsessions. For our part, we would need to show them that we don’t need games that fit neatly into pre-determined market niches. Like the categories of “casual” and “hardcore” themselves, defining a game’s genre is best left to marketing departments, not to players or designers.

Frankly, if I had the choice between imitating a yuppie who expertly orders a “triple-soy half-caff mocha latte” or an Italian plumber who dumbly rams his head into a mystery box, I’ll choose the plumber every time.